Santiago

Our Story

Establishing the post in challenging circumstances

New Zealand and Chile established diplomatic relations in 1948, with embassies opening in each other’s countries in 1972. The New Zealand government decided to open an Embassy in Chile as part of its economic strategy to diversify markets for New Zealand exports. Chile offered considerable potential for growth in a new trans-Pacific market.

This was New Zealand’s first post in South America. John G. McArthur became our first Ambassador to Chile accompanied by his wife Piera McArthur.

In her book Diplomatic Ladies Joanna Woods sets the scene:

“Despite the lure of a lucrative milk powder deal, the government could hardly have chosen a worse moment for its first venture in Latin America. Stirred up by the economic reforms of President Salvador Allende, Chile was in a state of turmoil…. By October 1972, waves of strikes were paralysing the country, inflation was soaring and rumours of a coup d’etat were rife”.

It was at this time that the Ministry’s Counsellor Don Hunn was tasked with setting up the Santiago mission. Don was expecting a shortage of housing, a problem he had recently experienced when setting up another mission. The Australian mission kindly offered a co-location arrangement with New Zealand, and the Canadians offered offices in the CBD not being used at the time. However, New Zealand was keen for a high degree of self-sufficiency and independent identity for the chancery premises. With thousands of wealthy Chileans fleeing the country, Don was able to acquire two enormous houses to accommodate the staff, and a charming European-style building for the office costing US$50,000 in the suburban area of Barrio Alto.

Woods picks up the story:

By the time John presented his credentials to Allende in March 1973, Chile was lapsing into chaos. Thousands of women marched through the streets, banging their empty saucepans in protest at the food shortages, and Piera remembers seeing truckloads of workers waving pitchforks heading off to take over the ‘estancias’.

In September 1973, General Pinochet led a military coup to overthrow the democratically-elected left-wing government of Allende.

Woods describes what happened next:

It began early on 11 September and Piera remembers John ‘skidding round the corner from the bathroom, still shaving, shouting “it’s happening. It’s happening”’. From her bedroom, Piera could hear the planes passing overhead on their way to bomb the Presidential Palace . . . and Allende’s Official Residence. Within a couple of hours General Pinochet and his troops had gained control of the country, but Allende and his supporters held out at the Palace until well into the afternoon...

After the coup . . . Santiago was overrun with people trying to evade capture. The most prominent were being hotly pursued and anyone who could claim political asylum was looking for an Embassy where they would be safe from arrest . . . it was only a question of time before someone approached New Zealand.

Piera’s eyewitness account continues:

One Sunday morning John got a call from the guard at the Embassy to say that someone had broken in. He went off in the car to see what had happened ... He rang me at home saying “I’m coming home and I’m bringing someone with me. I want you to stand at the gate and make sure the coast is clear.’... Eventually his car came down through the gates into the courtyard, then across the cobbles and into the garage. Out got a hefty figure that looked rather like a Belgian charwoman with a wig and a hat and an astrakhan coat. He bowed to me graciously and said in very good English, ‘Madame, I ask your forgiveness for arriving in such a manner’.

Once he removed his disguise, Piera recognised the man immediately. It was the leader of the Trades Union Movement, Figueroa, one of the ten most wanted men in the country ... Piera showed him to a bedroom on a side of the house that was invisible from the street and for the next ten days he lived with them ... But, as far as asylum seekers went, Figueroa was quite a catch and before long Piera and John were able to hand him on to the Swedish Ambassador ... who was collecting political figures enthusiastically.

Period of transition

New Zealand continued diplomatic and trade relations with Chile during the military dictatorship, despite a trade ban by the New Zealand Federation of Labour, which saw protests in the 1970s and 1980s.

The political relationship between New Zealand and Chile though was static for most of the 70s. It was only in the late 70s when a more normal pattern of relations began, although New Zealand continued criticism of Chile’s performance on human rights as demonstrated by our vote in the UN assembly in 1979.

The New Zealand Embassy’s main contact with the Chilean government was on trade and Antarctica. And although inflation and political turmoil halted earlier dairy export hopes, there was continuing interest from both the New Zealand and Chilean business communities for trade. The year 1979 saw a trade mission to Chile and cooperation on forestry and agriculture between the two countries continued. Geothermal development in Chile also offered good prospects for New Zealand involvement.

The Pinochet government gradually permitted greater freedom to participate in trade union and political activity. In the 1980s, due to economic collapse and civil unrest, market-oriented reforms were launched and Chile moved toward a free market economy. The Christian Democrat coalition came to power in the 1988 election with President Aylwin serving from 1990 to 1994, in what was considered a transition period.

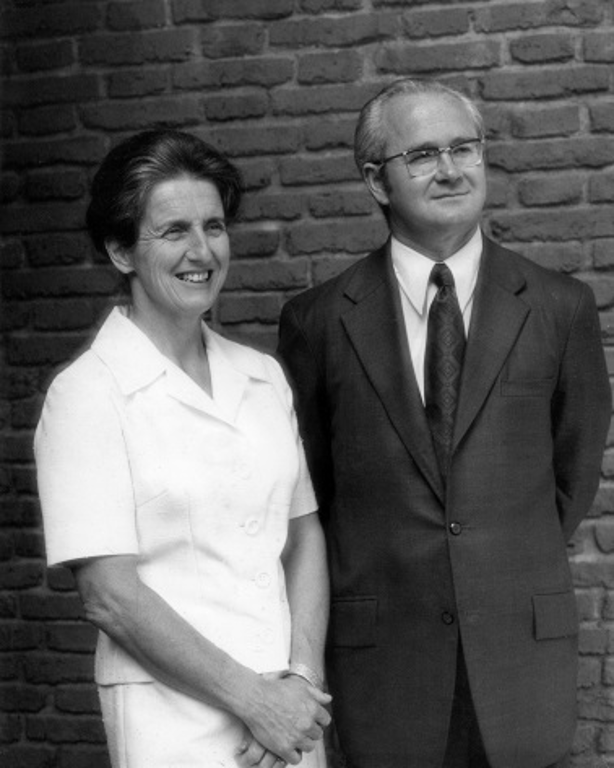

Piera and John G. McArthur, New Zealand Ambassador to Chile (1973-1975), Santiago, 1973.

Credit: Piera McArthur

Forging a close relationship in a new era

The bilateral relationship between New Zealand and Chile strengthened in the late 1990s through regular engagement at both official and ministerial levels. In September 2003, Singapore, Chile and New Zealand held the first round of ‘Pacific Three’ or ‘P3’ negotiations. The three countries joined together with a common vision of a high ambition, comprehensive trans-Pacific trade agreement which others would want to join. This common vision culminated in the signing of the ‘P4 Agreement’ when Brunei joined at the last negotiating round. The P4 became the platform for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and later for the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

New Zealand and Chile have continued to forge a close relationship, the most established we have in the region. New Zealand’s Ambassador to Chile (2015-2018), Jacqui Caine, says “we have very similar values to Chile and as small exporting countries, face a lot of the same challenges”. New Zealand is now negotiating a free trade agreement through the Pacific Alliance, the world’s sixth largest economic bloc, and we work together in a number of multilateral fora such as the United Nations and World Trade Organisation.

New Zealand and Chile have strong connections on agricultural cooperation, energy/geothermal, education and there is a working holiday exchange scheme for young people. We discuss topics as varied as immigration policy, gender equity, and how the New Zealand public sector is organised. Chile is interested in learning more about these areas from New Zealand’s own experience.

A focus is also on strengthening indigenous engagement, and for Jacqui “being a Māori ambassador has opened the door for a conversation with indigenous groups that might not have happened otherwise. I think there has been a curiousness about the fact that New Zealand has Māori ambassadors.”

Credit: Presidential Press, Government of Chile, 2015.

As part of this focus, an exhibition of Māori art and culture – Tuku Iho: Living Legacy – was held in Santiago from March to May 2015. This was the largest exhibition of Māori art and culture to be presented in Latin America and received over 26,000 visitors.

The exhibition was the culmination of 12 months of planning and collaboration between the New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute and the Embassy in Santiago working with Chilean institutions. It involved a wide-range of activities including artists carving four metre pou, a tattoo artist practicing ta moko, and Kapa haka performances and weaponry display and poi. One of the highlights of the programme was a traditional hangi held at the New Zealand Residence.

The event proved to be both a rewarding but also challenging experience.

Eight weeks after I arrived at post, we hosted the Māori Arts and Craft Institute (MACI). This was a major logistical exercise with lots of different challenges. This involved exporting a one tonne totara to Chile, which included some long conversations with the Ministry for Primary Industries about the tikanga (rules) around uncut wood leaving New Zealand, and shifting it around downtown Santiago in the middle of the night so that it could go to the museum.

We also decided to lay a hāngi in the middle of the residence lawn, with the assistance of experts from the MACI. It was the first time a hāngi had been laid for a number of years and the logistics of cooking for 170 people were complicated. It was a big project to manage for a small post, but offered us the opportunity to demonstrate manākitanga and host the New Zealand community in Chile, MACI and Rapa Nui representative at the Residence, and for me personally it was a wonderful way to commence a posting.

Opening a post in Santiago in 1972 provided an opportunity for growth in a new trans-Pacific market. While this started under challenging circumstances, the New Zealand-Chile relationship has grown based on mutual values and outlook. Chile is now a key partner for New Zealand in Latin America.

Hangi at the New Zealand Residence, 2015.

Source: Joanna Woods, Diplomatic Ladies: New Zealand’s Unsung Envoys (Otago University Press, 2013).