The face of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

For Kiwis in difficulty overseas, our consular staff are a helping hand in times of need.

Early in the Boxing Day morning of 2004, a young man and woman are walking along the beach in Phuket, Thailand. She mentions how curious it is that the seawater has suddenly vanished. Intrigued, they walk up to the shoreline. Then they see a tower of water barreling in.

It’s a tsunami.

The couple sprint for cover.

They find a tree and clamber up, even as the first of the waves crashes in — claiming the life of the woman. Somehow her companion survives.

At an emergency shelter in the Thai resort, one of the first things he will see after the tragedy is the face of a consular officer from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

It’s a face that has been seen by tens of thousands of New Zealanders experiencing distress abroad over the past 75 years.

The emergencies that consular staff members deal with come in all shapes and sizes. Sometimes it's as vast as the waves that struck parts of Thailand and five other countries in 2004. It may be a war, a threatened epidemic, or coordinated terrorist attacks in a major world city.

Most of the crises are smaller. They may involve a lost passport or somebody who has been in a car accident or somebody who desperately needs to know where he can watch the televised coverage of an All Blacks fixture.

Often it will be the work of ensuring that a New Zealander abroad has received legal assistance.

Lyndal Walker, a former director of the Consular division who also headed the emergency effort to locate missing New Zealanders in the wake of the Boxing Day tsunamis, says consular services are the Ministry’s storefront window. Much of what is displayed in that window has changed over time.

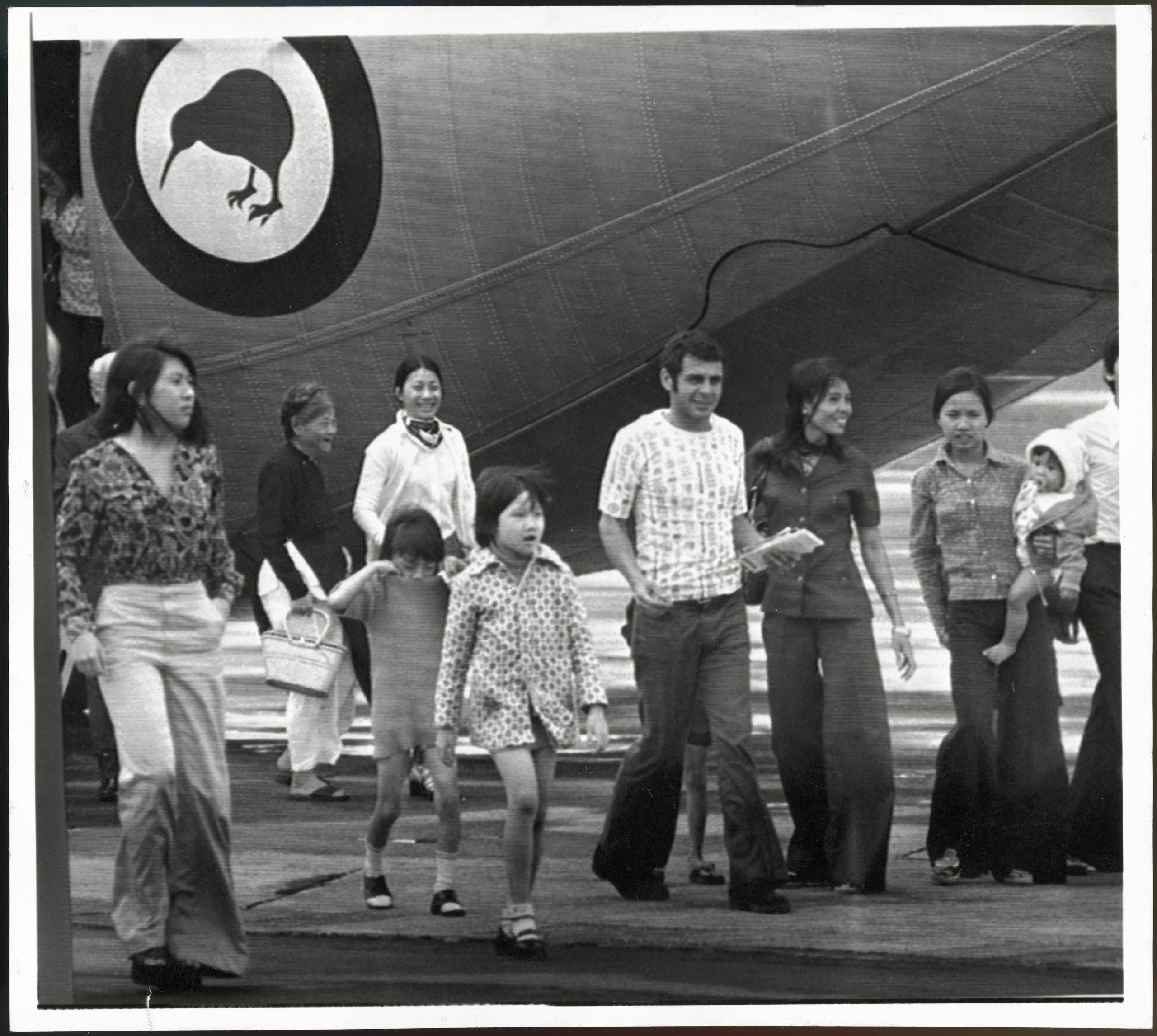

The Fall of Saigon

In 1975, all eyes were on the miserable conflict in Vietnam, and the fate of those who might be evacuated ahead of the fall of Saigon.

Frank Wilson, a veteran diplomat, was then on his first posting in the capital of what was South Vietnam. He arrived in Southeast Asia two years earlier to work on Overseas Development Assistance, along with the occasional consular role. The “occasional” work was to consume his life; 45 years on, he still speaks of it as the most dramatic interlude of a jam- packed career.

He remembers for instance, the drama involved in just one of a significant number of rescue operations, this one involved saving three nuns who got caught up in the hostilities.

"And they’d been in prison camps and moving across country. They were in pretty bad shape. And we received them. And then the South Vietnamese military wouldn’t let them go. They said "these people, they might be nuns, but they must be spies; how come they have come across from the enemy side? We don’t trust them. We want to interrogate them, we want to imprison them".

Anyway, after a lot of argy bargy, I said "I’ll take responsibility". So I signed a piece of paper in Vietnamese which said ‘I, Frank Wilson, Third Secretary at New Zealand Embassy, Saigon, have received in good condition, three nuns. And I vouch for them’. And I gave them this piece of paper, and it seemed to do the trick."

Vietnamese of a certain category were looking to get out quickly, Mr Wilson says, and New Zealand was seen as a highly desirable destination.

Thanks to the Colombo Plan, a multinational education exchange for promising Asian students, a number of New Zealand women with Vietnamese husbands were living in or near Saigon. Due to an anomaly in the law, this did not automatically give their husbands the right to relocate to the South Seas. Even for those who did have the right, there was the issue of Vietnamese males between 16 and 60 being liable to be drafted.

As the fall of the city drew closer, Mr Wilson found himself the middle man between increasingly desperate Vietnamese supplicants and a team of government officials back in Wellington helping to sort out eligibility.

It was “heartrending”, Mr Wilson says, recalling “the tears and floods of emotion” they had to deal with when interviewing hopefuls — a never-to-be-forgotten of piece of consular work at its most harrowing.

"These were people whose lives were in jeopardy."

Waves of Shock

The undersea megathrust earthquake that struck on Boxing Day, 2004, was one of the biggest consular challenges to date. Subsequent tsunamis crashed into most countries bordering the Indian Ocean, notably Indonesia, Sri Lanka and the popular Kiwi holiday destination of Thailand.

It also sent waves of shock into the Ministry.

“This was a crisis that hit us after 9/11 and after the Bali bombing, Which is to say, a time when we had moved our emergency system and practices forward quite a long way. But any event like this, something that is utterly off the scale of the known — whether it’s a once-in-a-thousand-year flood or whatever — doesn’t just hit the system. It bends the system. It stresses the system. As the shock is absorbed, the question is whether they will be able to stand again.”

Simon Murdoch, Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade at the time of the tsunami.

The Boxing Day tsunami also imparted “important lessons on what to do in the event of a mass disaster involving many New Zealanders.” Ultimately, Mr Murdoch believes, it strengthened the operation.

He was at home when the news first broke. “I remember turning on CNN and seeing the initial footage. And I just thought, Wow. The duty officer and I talked, and I realised I needed to go into the Ministry and consult with the team.”

The team he assembled arrived in the middle of the evening and immediately went to work.

For the next 24 hours, the challenge was to ensure the basic systems were up and running. Maintaining contact with the relevant posts, particularly Bangkok, where the ambassador and his deputy had also been away for the Christmas break, was also critical.

The Ministry’s 0800 number was overwhelmed with frantic callers. A decision was hastily made to implement an MOU with the Red Cross, who took over the calls.

There were “massive” problems, as well, with managing data. Another testing challenge was the Ministry’s ability to work with an interagency team that the Government dispatched to Thailand.

Interestingly, it would be the first occasion the response to such a crisis had been handled from the relevant ministry headquarters rather than inside the Beehive, with staff sewing together what tiny pieces of information they could gather about New Zealanders who may or may not have been affected.

“Can you imagine,” Mr Murdoch asks today, “trying to pinpoint the exact whereabouts of somebody about whom we only knew they had left somewhere the previous day and may or may not have been heading to Phuket?”

Image 1: Crisis Centre at Phuket Town Hall during Boxing Day Tsunami in Aceh Province, 2004. Courtesy of Jeremy Palmer.

Moana Dunn, who joined the Ministry in 1998, can imagine. Ms Dunn was in Samoa eleven years later when a similar disaster saw the island nation walloped by both a massive quake and a deadly tsunami on the morning of September 29, 2009.

Even for somebody used to life in the shaky New Zealand capital, she says, the 8.1M temblor felt powerful — powerful enough for her to move at lightening-fast speed to scoop up her then five-year-old daughter and dive under a door at the High Commission compound.

The tsunami occurred in the southern coast of Samoa’s main island, Upolu – where tidal waves struck the Falealili and Aleipata Districts.

As staff quickly gathered at the residence of the Deputy High Commissioner, the enormity of what had occurred began to register.

Staff members fanned out to assist on a number of urgent fronts. Local staff not affected by the incident were able to make their way into the office to provide much needed assistance for New Zealanders who were turning up at the High Commission compound. Family members of High Commission staff were also helping out.

Visiting New Zealanders (and dual nationals), many of them still in their pyjamas, required transportation to help them get out of devastation’s way.

Families in New Zealand wanted to know about loved ones in Samoa — and vice versa.

New Zealand Police had to be consulted in the identification of bodies.

Five MFAT staff were also dispatched to Samoa aboard a Royal New Zealand Air Force plane.

Work continued on that first day until 1am.

Business for the next day resumed just three hours later.“I was sitting at my desk when Moana first called in,” says Jan Kerr, taking up the story from the Wellington end, “and she was talking about the earthquake when the tsunami came in, too. Then we lost communication. I remember it so well. I remember the drama of working around the clock, with those in Samoa being in the High Commission.

It was simply impossible to put the phone down and leave it down. Immediately it would ring again. And again.”

All calls at the time were handled by the division rather than a dedicated centre. “And these just weren’t ordinary calls,” Ms Kerr points out. “Each one had to be taken seriously. It was … well, let’s say it was pretty full-on.

In a sense, though, the emergency side of consular work is simply a dramatised version of the smaller crises that consular staff members grapple with on a daily basis.

Today there are more Kiwis in dangerous environments and potentially parlous situations overseas, not only in terms of disasters and conflict but the growing appetite for adventurous tourism and business operations in higher-risk environments.

No longer do old assumptions hold that emergency situations happening in once-obscure regions — South Sudan, for example, or South Lebanon — meant few or no affected New Zealanders to consider.

The complexity of case management has also increased, aggravated by increasingly prevalent issues such as multiple citizenship, child abduction across legal systems and terrorism.

“The nature of consular work can be challenging and often no two days are the same,” Ms Dunn points out.

“In Samoa, for example, it can range from a lost or stolen passport to assisting domestic violence cases — cases where a woman might be sleeping out on the beach with her kids. Now that’s not a natural disaster — but it’s certainly an emergency. In a situation like that, we might sometimes need to work with a number of agencies to find good outcomes. And that’s also what’s satisfying about any kind of consular work, whether in an emergency or in day-to-day management — finding good outcomes.”

Moana Dunn, Administration Manager Bangkok

In the case of the Samoa tsunami, a “good outcome” was the establishment of an emergency coordination centre at the Ministry.

This works alongside other local government agencies and indeed other governments.

“The systems have improved over the years,” Ms Dunn notes, “but the workload has increased, too, in an era where so many people are travelling. We must also keep up with the times.”

Hard Lessons

Image above: Diplomat Jeremy Palmer standing in remains of Sari Club – site of the 2002 Bali Bombing. Courtesy of Jeremy Palmer.

Rosemary Paterson, a former director of the consular division from 2005 to 2009, came to the division six months after the Boxing Day calamity. She therefore did not so much experience the tragedy as the lessons it imparted.

Four days into her new position, in July 2005, Ms Paterson helped coordinate the response to the terrorist bombings of the London transit system.

Shortly after, as well, there was a second Bali bombing, a 34-day conflict between Lebanon and Israel (prompting one of the biggest international evacuations of recent history), a coup in Fiji, various earthquakes, the Mumbai terrorist attacks, the Air New Zealand plane crashing off the coast of France “plus a couple of high-profile hostage-taking incidents in the Middle East”. The experience has been in “putting into practice the lessons learned,” Ms Paterson notes.

“We became very good at setting up the Ministry crisis centre. Consular was a small team, so part of the work was finding volunteers among the staff."

While managing these crises the Consular team also launched its Safe Travel campaign. This included a major revamp of the Ministry’s travel advisories, a programme of outreach on safe travel overseas and the establishment of an advisory panel comprising the travel industry, airlines and the insurance industry.

The five-nation partnership between New Zealand, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and United States has been a strong feature of the Ministry’s consular responses. They also work together when there is a disaster or emergency and on case management in situations where one country is not represented and another is.

Sometimes it will be New Zealand relying on these other partners — as happened during the most recent Israel-Lebanon war, where the British included New Zealanders on the vessels evacuating from Lebanon to Cyprus.

Sometimes it will be the others who rely heavily on New Zealand — as they did in the case of the Canterbury earthquake in February 2011.

Lyndal Walker has enjoyed a bird’s eye view of the changing times. Ms Walker, former Ambassador to The Netherlands, began in the Ministry in the 1980s, when her first posting was to Rome.

Every Monday morning she would see a small queue of Kiwis outside the Embassy waiting to report lost passports or belongings or “because they were like ET and wanted to phone home for more money from mum and dad”.

Today thanks to the internet, travellers have become more self-sufficient.

Posted in Bangkok, she later led the New Zealand response in Thailand to the tsunami — a harrowing time in consular and humanitarian terms, but significant professionally in that it was the first time NZ Inc (the name given to a number of the country’s government agencies that work together to promote New Zealand abroad) worked in unison in the wake of a natural catastrophe.

According to Ms Walker, technology has been a two-edged sword as it has sought to manage the expectations of governments, families and media in times of crisis.

It has helped the Ministry in terms of its website activity, online interaction with people, around three-quarters of whom have consistently told independent pollsters they were treated well. Satisfaction levels with the Safe Travel website — which has logged 570,000 registrations by traveling Kiwis over the past four years — are around the same.

The consular story continues to be disseminated across platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. Social media outlets like these provide their own “check in” assistance during times of crisis by being immediate ports of call for those who might once have contacted the nearest mission.

“These days during a major emergency,” Ms Walker notes, “we find the phone still runs reasonably hot — but not piping hot.” “If caught up in a major event, most kiwis tend to quickly email, text or Facebook home that they are OK. We tend to receive only calls of genuine concern if someone is missing or injured.

The Ministry has tried to juggle the rising demand for hands-on consular services with greater cautionary advice to travellers — especially when it comes to warnings about the limits to government support for those who find themselves caught in a predicament. At the same time, it has beefed up its partnerships with other government agencies, the private sector NGOs and other governments.

Technology is also about online news outlets and social media. Overseas, studies have shown that these have provided good coverage for foreign ministries when they demonstrate the capacity to rescue citizens.

However, criticism that the Ministry is not doing enough during stressful times or in highly emotive cases can also become a high profile media story, even though the Ministry is usually constrained by privacy reasons from discussing the situation publicly.

“We’ve spent a lot of time engaging with the media, promoting SafeTravel and explaining ways for people to keep safe — and with that activity comes a natural increase in profile,” says Ms Kerr.

“So, obviously, we’ve also worked hard for it to be known that the Ministry doesn’t have a fund of money to bail out New Zealanders in trouble overseas …But I have to say, we are having less and less of that now. People know what we do, and what we don’t do, and that’s critical as we continue moving forward.”

Lyndal Walker, former New Zealand Ambassador to The Netherlands

And continue to prepare for the next calamity — whether a natural catastrophe, an outburst of international violence or a passport somebody thinks they may have lost at a foreign nightclub.