Antarctic haven

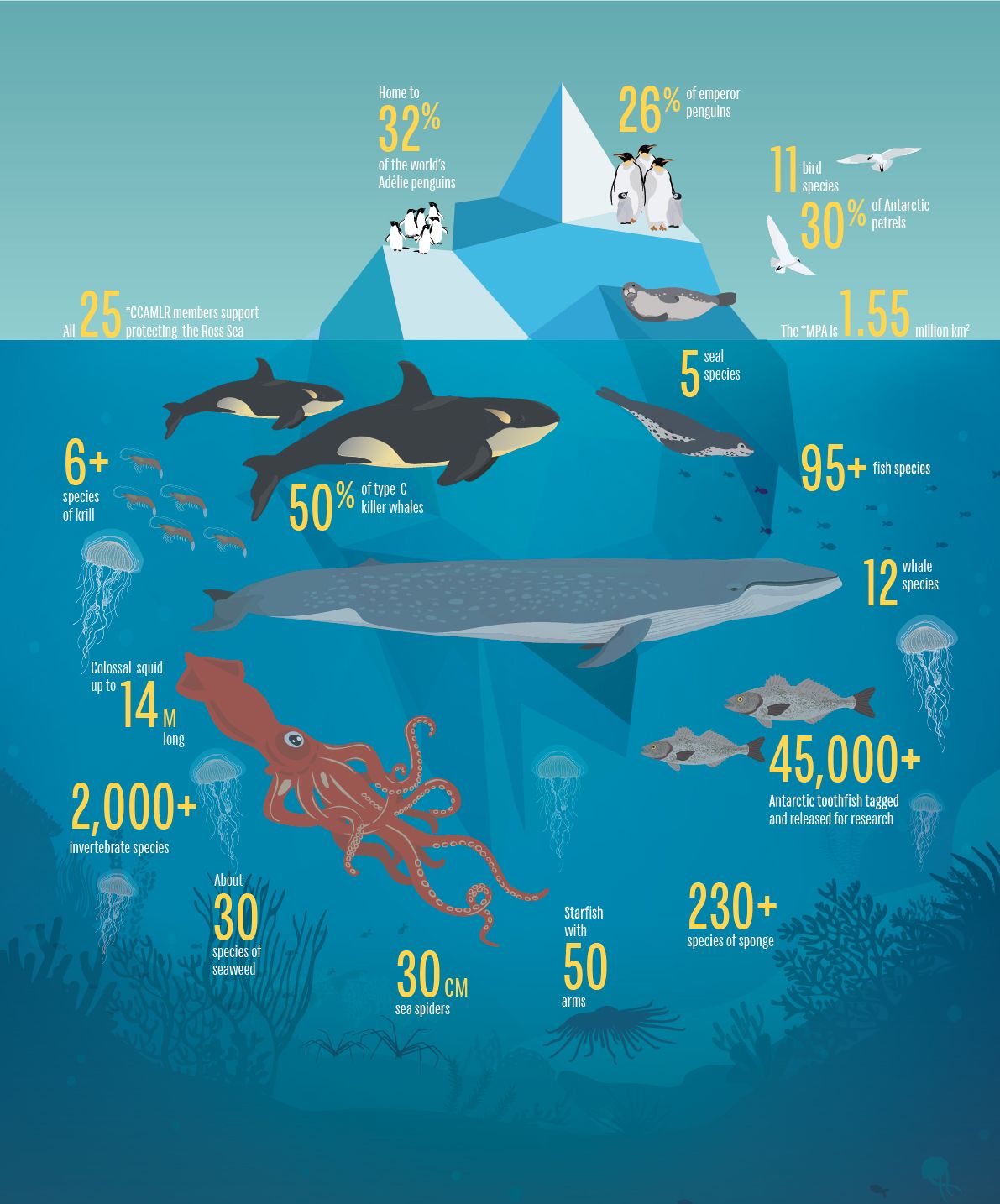

The world's largest Marine Protected Area covers the Ross Sea region of Antarctica.

New Zealand, together with the United States, played a leading role in creating it.

Head directly south from New Zealand for 3000 kilometres and you’ll arrive at the Ross Sea.

It’s a vast, pristine stretch of the Southern Ocean that’s been called the “least altered marine ecosystem on Earth".

Unusually among the world’s seas, it is still home to an unbroken food chain – from its full suite of predators, like killer whales and Weddell seals, down to microscopic plankton species.

The region is one of the world headquarters of the penguin: a million pairs of Adelie penguins live there (one in three members of the species), alongside a quarter of the world’s Emperor penguins.

Every summer, as the ice over the Ross Sea melts, the region experiences an explosion of new life, starting with ice algae and tiny plant species, which in turn feed clouds of krill, the tiny crustaceans who become fodder for Antarctic silverfish, and on and on up to a teeming mass of fish, bird, seal, squid, whale and other species.

Even the creatures that live in the freezing depths of the Ross Sea are extraordinary. The colossal squid famously on display in Wellington’s Te Papa museum was found here.

Hundreds of sponge species, some of which are thought to live 500 years or more, are part of the underwater landscape.

Likewise, hundreds of metres below the penguins, Antarctic toothfish roam the water, the major fish predator in an area with no sharks. They're prized as delicacies on global restaurant tables, where they're sold as "Chilean sea bass". They're also one of the chief beneficiaries of a historic new development for the Ross Sea.

From 1 December 2017, a watershed agreement to protect the area will be in force.

The Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area covers a stretch of water six times the size of New Zealand.

It’s a breakthrough for the Southern Ocean – and it’s a powerful model for how countries can agree on protections for international waters, the enormous lengths of the world’s seas and oceans that are under the jurisdiction of no individual country. At present, only about 0.5 per cent of these waters are protected.

"The Ross Sea is one of the most remote and remarkable stretches of ocean on the planet."

Peter Young, The Last Ocean filmmaker

About 1.12 million square kilometres of the Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area (MPA) will be fully protected. An area nearly half that size again will allow limited, carefully monitored fishing. This allowance was necessary to secure the agreement – and it will also improve understanding of how sustainable fishing affects the region's ecosystem.

New Zealand played a critical role in the new protections for the Ross Sea.

The history

Named for the British explorer James Ross, who arrived in the summer of 1841 on an unsuccessful journey to the South Pole, the Ross Sea is among the most productive stretches of Antarctic waters.

Bordered to the south by the imposing Ross Ice Shelf (the largest on the southern continent), the sea is frozen over for much of the year. Explorers from Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen onwards have used the area as a launch point or supply route for their ventures to the South Pole.

With multiple nearby research facilities, including New Zealand’s Scott Base, the Ross Sea is also among the best-studied of Antarctic waters, with data that goes back many decades. This is one reason it is an especially useful site for research on climate change.

New Zealand’s interest in the area goes back a long way too – the Ross Sea is part of the Ross Dependency, which New Zealand inherited as a territorial claim from the United Kingdom in 1923.

All of Antarctica is now governed by the Antarctic Treaty, which suspends territorial claims and commits all signatories to using the continent for peaceful purposes alone.

Complementing the treaty is the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, established in 1982 in response to increasing commercial interest in the Antarctic’s krill resources and the over-exploitation of other Southern Ocean marine resources. The convention allows for sustainable fishing that takes into account effects on other parts of the ecosystem.

Each year, a commission in charge of the convention meets to work through new rules and proposals for doing this.

The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area, agreed against expectations in 2016, was a historic step for the group, which includes 24 member countries and the European Union and makes its decisions by consensus. It was by far the largest protected area they had agreed on.

Who’s got a stake in the Ross Sea?

All sorts of people, for many reasons.

Conservationists want to protect what’s sometimes called “the last ocean” for its spectacular marine ecosystem.

Scientists, New Zealanders central among them, want to study the wildlife and wider environment of the Ross Sea. They want to ensure the fisheries remain sustainable, and that fishing doesn't harm other parts of the ecosystem. They’re also eager to keep learning about climate change in a key site for understanding this urgent global challenge.

Fishers from a range of countries, including New Zealand, want to catch Antarctic toothfish, which command high prices around the world. They’ve done so in the area since the mid-1990s.

"You have to remember that the Ross Sea fishing area is covered by ice for nine months of the year – so for nine months of the year the whole area is a natural MPA."

Greg Johansson, chief operating officer, Sanford

Finally, a broad group of countries wants to work together to balance these interests, keep a magnificent part of the world in good health, and preserve Antarctica as a place for peace, research and conservation.

New Zealand's role

Creating the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area meant listening to all of these viewpoints and finding a compromise solution.

New Zealand played a leading role in this journey. Work first began on the idea of an MPA in 2005. Seven years later, New Zealand and the United States took a proposal to the body that decides on such areas (the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, or CCAMLR).

Progress was at times painstakingly slow. Moving forward took a sustained effort from New Zealand’s public agencies and Minister of Foreign Affairs.

The Ministry for Primary Industries led on the fisheries science that came to underpin the MPA. This was critical – it’s the basis for New Zealand's confidence that the fishing in the MPA will remain sustainable, and it was also the key to convincing other countries, with widely varying perspectives, that the final proposal was the best bet for the Ross Sea.

The Department of Conservation provided conservation science and advice, NIWA also provided scientific research and fisheries information, while the New Zealand Navy will continue its Southern Ocean patrols during the fishing season to enforce international rules and fight against illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade led the international diplomatic effort – negotiating the details of the MPA with other CCAMLR countries and working in the background over several years to build support for a deal.

A sudden breakthrough

By 2016, years of meetings had ended without agreement on a Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area. Even the optimistic were beginning to doubt it could be achieved. Few of the leading diplomats at that year's meeting thought they were on the verge of success.

Here’s how Jillian Dempster,who was New Zealand’s Commissioner to CCAMLR at the time (the top Kiwi official working on the MPA), remembers the October 2016 meeting:

"As a diplomat involved in multilateral negotiations, I know all about slow progress – or, as I sometimes call it, bashing my head against a wall – but this felt like no progress.

Even though we had a viable proposal, put forward jointly by New Zealand and our partners the United States, and even though our science was detailed and sound, it looked like we wouldn’t persuade everyone. That means failure, because a new MPA needs consensus from all 24 member countries and the European Union.

But then, in the middle of last year’s meeting, the landscape changed. Russia, which had opposed the MPA for several years, suddenly said it was open to negotiating a deal.

I remember the day clearly. First there was the sheer surprise – you could hear a pin drop when we got the news.

That gave way to a fresh momentum. With a huge amount of technical work still to do, we went into what would usually be a dry, laborious meeting. But this one was the opposite: we began agreeing on key details one after the other, like magic.

Many factors and many years of effort led to that moment. While Russia was the last to agree, it wasn’t all about one country. It was mostly about years of hard work and determined, creative diplomacy – from New Zealand’s substantial, ongoing investment in Ross Sea science, to quiet meetings in the corners of CCAMLR, to arguing our case in capital cities around the world, to agreeing on major concessions with many countries. Advocacy from politicians, including former US Secretary of State John Kerry, was another critical factor late in the piece."

The Marine Protected Area

When the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area was agreed on, National Geographic called it one of the top five environmental achievements of 2016.

Conservationists like Peter Young, the filmmaker behind The Last Ocean, backed the MPA after years of working to draw attention to the Ross Sea.

Countries and companies with fishing interests in the area have also supported the new protections.

"This decision represents an almost unprecedented level of international cooperation regarding a large marine ecosystem comprising important benthic and pelagic habitats."

Andrew Wright, CCAMLR executive secretary, in 2016

Key features include:

- Its sheer size. At 1.55 million square kilometres, the Marine Protected Area is about twice the size of the US state of Texas. It’s also the largest protected area on land or sea – half as big again as the world’s largest national park on land (in Greenland). It protects about seven percent of the Southern Ocean.

- Its wide “no-take” zone. Commercial fishing is prohibited in about three quarters of the MPA, including the main nursery grounds for juvenile and sub-adult Antarctic Toothfish, a key goal of the agreement.

- Its research zones which allow limited, monitored fishing, including for krill and toothfish. These were necessary to win agreement on the MPA from all 24 countries and the European Union in CCAMLR.

- Its emphasis on robust science. The deal requires ongoing scientific research, with regular updates to check the MPA is working.

What's so special about Antarctic toothfish?

Sometimes called "white gold" because they are so valuable, Antarctic toothfish are the largest fish predator in the Ross Sea region.

"Toothfish are at the top of the food chain. They're kind of like the sharks of the Southern Ocean system. They're the largest, most voracious predators in the Southern Ocean, in the marine sense."

NIWA principal scientist Matt Pinkerton

They're famous for the "anti-freeze" proteins that keep their blood from solidifying in their icy habitat. They also lack a swim bladder, which most fish use for buoyancy. (Toothfish just have a lot of fat, which is also part of the reason they are so prized by fishers).

The toothfish begin life in shallower waters, but head for the deep as they get older. To study them, scientists typically need to cut through two metres of sea ice. Then they drop lines hundreds of metres below the surface to the pitch-dark, minus-2 degrees Celsius waters where the fish live.

Commercial fishers also have a major role in the scientific study of toothfish. They must tag and release some of the fish they catch. When those fish are caught again, scientists can monitor how much they have grown and their movements around the region. So far they've tagged and released more than 45,000 toothfish in the Ross Sea region.

Antarctic toothfish were first commercially fished only as recently as the 1990s. Today around 3000 tonnes can be taken annually from the Ross Sea region, but the fishery is regulated and the Marine Protected Area places important new restrictions on the areas in which they can be caught.

The road ahead

Most of the Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area (the fully-protected part) is set down to last for 35 years – at which point it will need another consensus decision to be renewed.

But long before that decision, a rigorous scientific research and monitoring programme will be needed to convince other countries and interests that the MPA is on track.

New Zealand is putting substantial new funding into its Antarctic science programme, partly to help meet the need for new science coming out of the Ross Sea MPA. We need to better understand how the region's ecosystem is affected by fishing, both inside and outside the MPA. Of course, we will also be keeping a close eye on the fishery to ensure Antarctic toothfish stocks remain sustainably managed.

We’ll keep listening to other countries, their own science, and their perspectives on how to look after the region.

"The protected area is in place for 35 years. It sounds like a long time – it’s not. We’re up against the clock to prove that the areas we’ve put forward for protection are the right areas to protect."

Amy Laurenson, New Zealand's former CCAMLR Commissioner

Meanwhile, our navy patrols in the Southern Ocean will keep monitoring the area to ensure CCAMLR's high standards are met, and to deter illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

More Marine Protected Areas around Antarctica are in the works, and we’re hoping the Ross Sea region MPA can be a model for these – and other ocean protections across the globe.

That is the job ahead.

For now, New Zealanders and people around the world can celebrate a unique and historic agreement – a deal made between 24 countries and the European Union to protect one of the world’s most spectacular stretches of water.

We think it shows what’s achievable with sound scientific evidence and persistent diplomacy – even when the odds look long.

The Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area took years of detailed work – and the occasional disagreement. We’re delighted that such a diverse group of people, countries and interests are backing it. We think it's something the world can take pride in.

With thanks to: The producers of The Last Ocean, The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Sanford, The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), Anthony Powell, Jason O'Hara, Dr Regina Eisert (University of Canterbury), Antarctica New Zealand, Ministry for Primary Industries, The Antarctic Office, The Australian Antarctic Division.

Photo credits: Emperor Penguins, Craig Potton; Flags, Dr Steve Parker, NIWA; Weddell seal, Dr Chris Darby, CEFAS; Starfish, Dr David Bowden, NIWA; Jillian Dempster, Doro Folck; Humpback whale, Jack Fenaughty, Sanford; Graphics, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade; Toothfish, Dr Sophie Mormede, NIWA; Landing toothfish, Dr Laura Ghiglotti, CNR; NZ researchers, Dr Ingrid Visser; Iceberg and penguins, Dr Regina Eisert, University of Canterbury.