Taking a nuclear-free policy to the world

Fighting for nuclear disarmament has been part of the day job for our diplomats for over thirty years.

New Zealand’s Ambassador for Disarmament, Dell Higgie, describes it as the issue that has “most dominated” our efforts at the United Nations – and that continues to this day.

Every now and then, Lucy Duncan thinks about how the diplomatic fight against nuclear proliferation has shadowed her working life.

Long before Ms Duncan first joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade — even when she was a kid growing up in Dunedin in the 1970s — the political air was heavy with nuclear fallout in the wake of Labour prime minister Norman Kirk dispatching a frigate with one of his ministers on board to protest against French nuclear testing at Mururoa atoll.

The move put the wind in the sails of the anti-nuclear movement and what would become the country’s signature foreign policy.

Six months after joining the Ministry, in 1984, Ms Duncan’s entrée to the diplomatic life was the arrival of the fourth Labour government.

The new administration had been elected on a historic pledge to change the way New Zealand did business with the nuclear powers.

A decade later

A decade on, Ms Duncan headed to the United Nations centres in Europe and the United States for a variety of roles relating to nuclear disarmament and arms control negotiation — even as New Zealand revived its major anti-nuclear case against France at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Today she sees how the country’s policy continues to reverberate with New Zealand’s trading partners in Latin America.

“If there’s one thing that every country knows about New Zealand, from La Paz in Bolivia all the way to Panama City,” she says, “it is our stand on nuclear disarmament”.

But nuclear disarmament is much more than the back-story to just one diplomat’s career.

As former prime ministers Sir Geoffrey Palmer, Jim Bolger, and Helen Clark — along with veteran activists, NGOs and historians — point out, it has been a crucial part of the country’s politics and culture for as long as most New Zealanders have been alive.

The fight against nuclear weapons provides one of the most sustained examples of the independence with which New Zealand has crafted much of its foreign policy over the past 75 years.

'We're New Zealanders'

New Zealand’s stormy history of anti-nuclear diplomacy dates back to the independence of colonial Algeria which spurred its one-time French colonial power to move its offshore military activity to the South Pacific.

Mururoa, an atoll 1250 kms southeast of Tahiti, became the site of France’s atmospheric nuclear testing. It also became a byword for New Zealand’s role as, in the words of former prime minister Norman Kirk, “the conscience of the world”.

Mr Kirk famously dispatched a protest vessel to French Polynesia and his government also petitioned the ICJ, for an end to the tests.

In 1973, the New Zealand and Australian governments, and some Pacific Island states took France to the ICJ. France refused to accept the court’s interim ruling that it must cease testing. But mounting international pressure forced the country to switch to underground tests in 1974.

Sir Kenneth Keith was involved in what would be the first case against the French, as one of a legal team of four working alongside their counterparts in Australia.

In addition to being a watershed diplomatic moment for the country, it would set the scene for much of the diplomatic activity up until the present day.

“The New Zealand view, as expressed by Prime Minister Kirk was: ‘We’re New Zealanders, we can do it, can’t we?’ And so we said, ‘Yes, sir!’ and did it.”

Such was the “general awakening, or at least the beginning of a general awakening” for New Zealanders of how the country occupies an independent space in foreign relations, according to Colin Keating, a former ambassador to the United Nations - at the time the Director of the MFAT Legal Division and charged by David Lange with personally drafting the anti-nuclear legislation.

Far from placating regional sentiment, as the French may have hoped, these continued tests intensified anti-nuclear feeling in New Zealand and Australia — and “I suppose the Americans ended up reaping that whirlwind,” Sir Kenneth says.

Winds of change

Helen Clark recalls those winds of change, too, first as a student at the University of Auckland in the 1970s and then as a young MP in the newly elected Labour government of 1984. “When Labour was elected, the nuclear-free position it had staked out was absolutely to the fore, and people expected that it would be implemented,” Ms Clark says today.

Her party had campaigned vigorously against nuclear weapons and propulsion, themes that picked up an urgent relevance ahead of the election when the National MP Marilyn Waring vowed she would support the opposition’s Nuclear Free New Zealand Bill. There had been, as well, a huge campaign by over 300 peace groups from the early 1980s onwards to push for the new policy.

Ms Clark chaired the Select Committee on Disarmament and Arms Control. "My recollection is that the Labour caucus was united around the nuclear-free policy — there was never any issue with that," she says.

“People wanted to see that policy upheld. And the truth also is that there were other very controversial things that government was doing while Roger Douglas was Minister of Finance, which were unpopular and, in a sense, holding onto the nuclear-free policy became even more important perhaps in that context."

The sticking point was the tripartite ANZUS treaty that New Zealand had been part of since 1951 (and which Labour had not campaigned in favour of abandoning). The country still wanted to be a part of ANZUS. But the arrangement also meant unpopular visits to the country from time to time by American warships.

Prime Minister David Lange attempted to find a compromise between visiting ships that could be nuclear-armed and those that may have only been nuclear-propelled.

This was a distinction others in the party were unwilling to live with, especially following the reactor explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Mr Keating recalls the immediate impact on the drafting of the anti-nuclear legislation. France sinking the Rainbow Warrior stiffened New Zealand determination. “One of the reasons the French came and sank it of course was because of the nuclear issues,” he says. The attack also resulted in a fatality.

The government found itself in a pickle. “What the Labour Party wanted was something the Labour Party couldn’t get,” Sir Geoffrey Palmer explains, “and that was to remain under the umbrella of ANZUS and enact the anti-nuclear policy. That was the sticking point. We attempted to have it both ways for as long as we could. David Lange, as foreign minister, certainly tried.”

Alas, says Mr Keating, “the centre of gravity had shifted” and the perceived need for legislation was now inevitable. The American administration "had no real appreciation of how hard it was for David Lange, working in a Westminster-type system, to bring his party along with him to a compromise." Mr Keating recalls a meeting he attended with the US ambassador of the time, in which Mr Lange was asked to be more "pro-active on the subject of a visit with the New Zealand public.

"David Lange leaned back and said, 'Ambassador, I would be grateful if you told your president that he stands for election once every four years; I am potentially up for election every Thursday at caucus.' “

A nixed visit to New Zealand by the USS Buchanan — an aging guided missile destroyer that might have been acceptable as a “compromise” visiting ship — took ANZUS into choppy waters. In 1987, the government passed nuclear-free legislation and the United States responded by downgrading the countries’ security ties.

Image 1: ANZUS meeting, May 1973. State Department, Washington DC. Front Row: Frank Corner (Sec. of Foreign Affairs), Arthur Faulkner (Min. of Defence), Lt Gen Richard Webb (Chief of Defence Staff), Lloyd White (NZ Ambassador to US) Back Row: Gerald Hensley (Counsellor), Dick Atkins (Minister), Unknown (Defence Attache), Lance Beath (Second Sec.), Michael Chilton (Second Sec.)

Image 2: The Rainbow Warrior at Marsden Wharf, Auckland, after the bombing of 10 July 1985. Photograph copyright to Greenpeace Photographer: John Miller

Image 3: Taranaki Daily News ‘ANZUS’ 1 October 1984. Lynch, James Robert 1947. Courtesy Alexander Turnbull Library.

The diplomatic path

As Mr Keating notes, the goal in the end had been to produce legislation that would allow a framework for negotiating the issue with the Americans “as well as something transparent for the public of New Zealand to see” — and on both scores the government delivered.

A new diplomatic path was set for the years ahead.

According to Sir Geoffrey and others from both major political parties, the foreign ministry did not start out as wildly enthusiastic advocates of this change in direction.

“But they were loyal public servants and did their best to advance it. Merwyn Norrish was the chief executive during most of this period, and he played a very straight bat. Tim Francis, his deputy, became a very strong advocate of the policy, too.”

Ms Clark remembers going to the New Zealand Embassy in Washington DC at that time, and encountering “some very long-faced” officials, who were starting to feel the diplomatic effect of doors slamming shut at the Pentagon, the US Department of State and National Security Council.

“But look, once the policy was determined and the red line was drawn, the Ministry got on supporting the government to carry out the policy. New Zealand has a small foreign ministry compared with so many countries. But we have fantastic diplomats. Once they know what the government position is, they go out and bat for it without blinking an eyelid. They are loyal to the government of the day. And what has been very helpful has been this continuity of positions among New Zealand governments on the nuclear-free issue.”

Helen Clark, former Prime Minister

At the time, of course, the nuclear issue was still somewhat politically divisive, in the way it had been a decade earlier when the opposition to nuclear weapons was often considered “left wing” — and opposed as such by the National Party.

Nevertheless, the party that had been “somewhat skeptical or a least by no means unanimous that that was the right thing to do” would eventually shift, says Jim Bolger, who as Prime Minister would inherit the anti-nuclear mantle during the 1990s.

By the time of the incoming National government of 1990, however, it was fully a bipartisan cause. This the country would need in the years ahead as Mr Bolger’s administration attempted, first, to improve relations with the US, while also ensuring New Zealand showed a united face to the world in the face of renewed French nuclear testing.

Image 1: U.S. Navy guided missile destroyer USS Buchanan (DDG-14) underway in 1983.

Image 2: Prime Minister Jim Bolger boarding the Tui in Auckland which supported a flotilla of protest yachts that travelled to the testing site at Moruroa Atoll in 1995. Credit RNZN Museum Reference: ACZ 0077

Testing times

After the suspension of ANZUS, the climate between New Zealand and the US was “pretty chilly,” Jim Bolger recalls with a bit of diplomatic understatement in 2018. The times were at least as cold as the freezing day in 1984 he spent as then Minister of Labour in Moscow with an American leader — in this case, President George W.H. Bush.

“I recall we spent a couple of hours together standing at minus-20 degrees in Red Square in Moscow for the funeral of President Andropov,” he remembers. “And of course we couldn’t understand a word of what was being said and so we had a lot of time to talk about the world in general including nuclear issues while others, I guess, eulogised the late president of Russia, or the Soviet Union as it was.”

Later as Prime Minister, attending UN Leaders’ Week in New York, Mr Bolger had the opportunity to meet again with President Bush.

“He had his senior security advisor with him, General Brent Scowcroft and I had a UN ambassador, Terence O’Brien, with me and you know we just talked through as sensible people knowing we had a big difference looking for ways in which we could advance the cooperation or understanding, or at least an understanding of each other’s position.”

That process of attending to this unfinished business, since fully resolved, would include Mr Bolger’s subsequent tenure as New Zealand’s ambassador to Washington.

In the meantime, five years into his three-term government, on June 13, 1995, France’s recently elected President Jacques Chirac, announced that his country would conduct a final series of eight nuclear weapons tests in the South Pacific.

The announcement also detonated something of a political bomb in Wellington.

Vctoria Hallum remembers the day the government of New Zealand decided to pursue a second ICJ case against France. For those in the Ministry’s Legal Division — not least Ms Hallum, a junior at the time —the legal case was neither obvious nor straightforward.

With the French counting down the weeks, time was also of the critical essence. Her manager at the time, Don McKay, was summoned to the Beehive to discuss the matter with some urgency.

“So I remember I was sitting in the division,” she says, taking up the story, “and the next thing I knew — an hour or two later — Don walks in, and as he passes my cubicle (we were in a sort of rabbit warren of little cubicles in that building), and I hear him say, ‘Well, we’re going to the International Court of Justice.’ And we were all flabbergasted. It was really a big surprise.”

Already, however, Mr Bolger had won the support of all of the parliamentary parties. “The Prime Minister thought this was an issue of such importance to New Zealanders, that it was relevant and appropriate to have a decision that all the parties in parliament supported.” It also ensured the team enjoyed wide support for the case it pursued.

The case was led by the Attorney-General Paul East, along with the Solicitor General, NZ Law Commission president Sir Kenneth Keith, with Ms Hallum there — as she puts it — “to carry the bags”.

She also helped carry the weight of the country’s expectations.

The last week, in particular, en route in Cambridge, England, all stops were pulled out to complete New Zealand's request for provisional measures — legal lingo for the country’s case.

She remembers arriving at the ICJ in The Hague to “a bank of television cameras that served notice that this was going to be a big deal … We had been very focused on marshalling the best arguments that it wasn’t until we got there that we also became aware of the glare of international publicity. It was exciting.”

It was unsuccessful. It was a complex case that turned on questions of jurisdiction and substance. The team was looking for the court to look at what was going on in 1995 as a continuation of the ICJ case New Zealand had brought against France 22 years earlier. They also argued that underground testing was against international law.

However, only three judges agreed among them Sir Geoffrey Palmer; 12 voted against New Zealand.

However, the case showed New Zealand being prepared to stand up in a principled way, and make credible arguments about something that was extremely important to the country and the immediate region.

I see a lot in these legal arguments that I recognise about the country that I represent today. I see a country that is committed to the rule of law, and to the sovereign equality of states— regardless of size and power — and I see a country that was willing to challenge one of our much larger friends in a court of law about something that we thought was fundamentally important. I see a country that is committed to international environmental law — and the progressive development of that law — and to the protection of the marine environment, and that’s something that’s been a consistent thread right through to today.

Victoria Hallum, the Ministry’s current chief international legal adviser.

Image 1: New Zealand Government Counsel during 1995 International Court of Justice Nuclear Test Case (New Zealand v. France)

Image 2: Victoria Hallum presenting at the International Criminal Court assembly of state parties meeting, December 2017.

Dr Kate Dewes, a co-director of the Disarmament and Security Centre in Christchurch, holds a more personal memory of another case, recalling as she does standing outside the court in the case to clarify the legal status of nuclear weapons, in November 1995 (known as the Advisory Opinion).

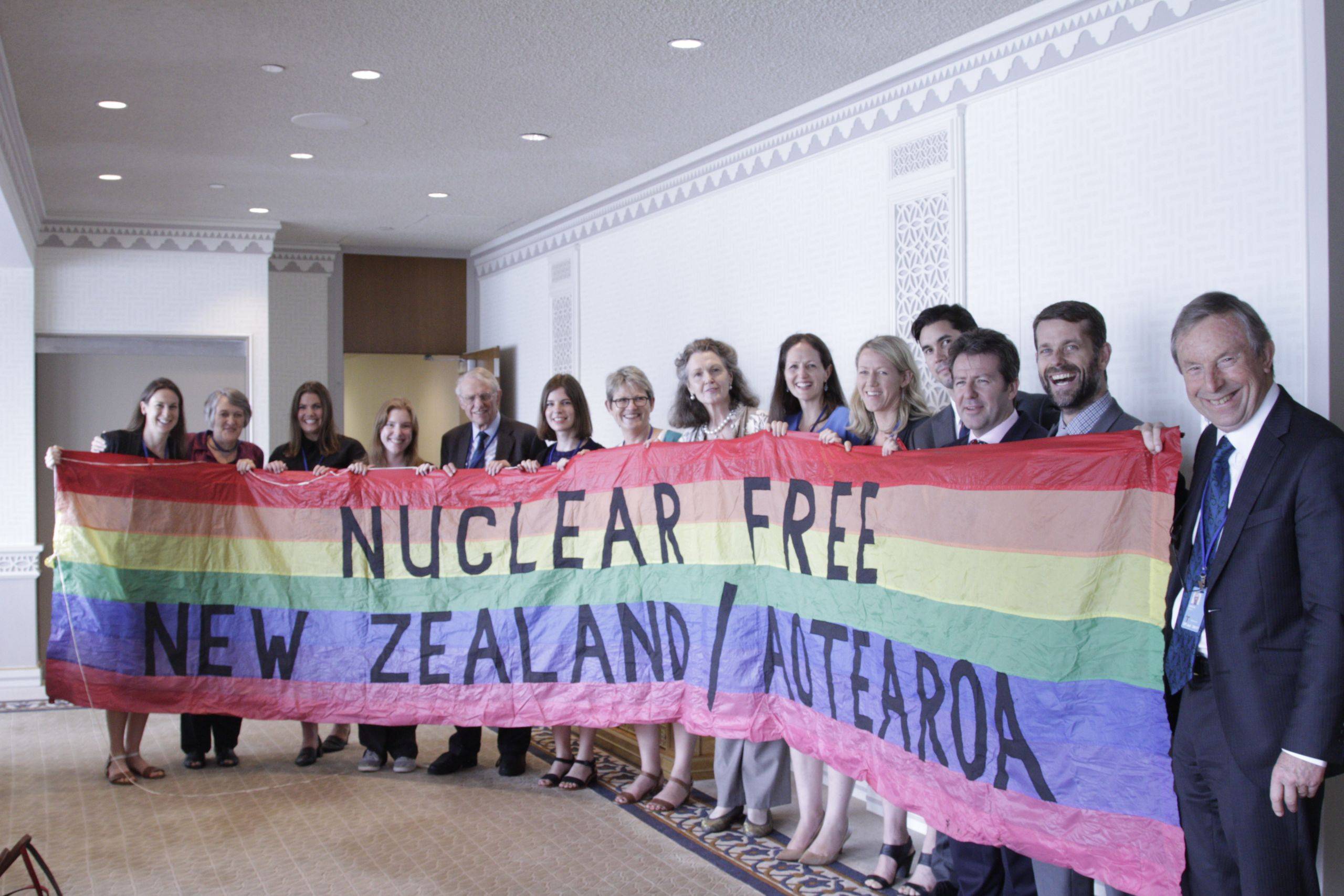

She shows a photograph of her with others holding a big nuclear-free rainbow outside The Hague.

“Now you’re not even normally supposed to have banners outside the Court. Those of us who’d helped take the case to the World Court were just standing in support of what was happening. And Paul East came over with our Hague ambassador at the time, and shook our hands over the rainbow. That morning he addressed the Court arguing illegality of nuclear weapons and added proudly, ‘The NGOs who started this project are here in the Court today and they’re from our country.’”

That case was ultimately successful with the Court delivering a landmark finding that a threat or use of nuclear weapons would “generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of international law.”

There also exists, the Court held “an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to complete nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control.”

Striking the right balance?

Of all the issues that the country's relatively small number of diplomats could have concentrated on, how important has this one been? Has the diplomatic fight for a nuclear-free world occupied too much time and energy? Or have we struck the right balance?

“I think we've got it right,” Ms Clark says in a widely shared assessment. “We're established as a champion of nuclear disarmament which still remains a very, very worthy cause.”

“With the rhetoric in 2018 around the North Korea nuclear programme, which of course is a worry, one starts to have that feeling again that it's not impossible that nuclear weapons could be used … [s]o we have to keep on — New Zealand is a standard-bearer for that position, we've long championed the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty, the nuclear-free zone in the South Pacific — we have to keep at it.”

For Sir Geoffrey Palmer, the critical point about New Zealand’s diplomatic anti-nuclear activism over the past 75 years is that it remains very much in the present tense.

“Yes, what happened in the 1980s was an epoch-making event,” he says of the original decision to go nuclear-free. “But it is significant still, of course, not only because we recently marked the 30th anniversary of the legislation, but also because the nuclear threat around the world right now is as bad as it has ever been — and getting worse.”

Mr Bolger agrees: “We did have a period not that long ago in world politics where in fact nuclear weapons were being destroyed,” he notes balefully. “But that seems to have slowed down or stopped altogether. And I think the whole debate needs to be energised again. It does require leadership from the big powers, but New Zealand can play a role.”

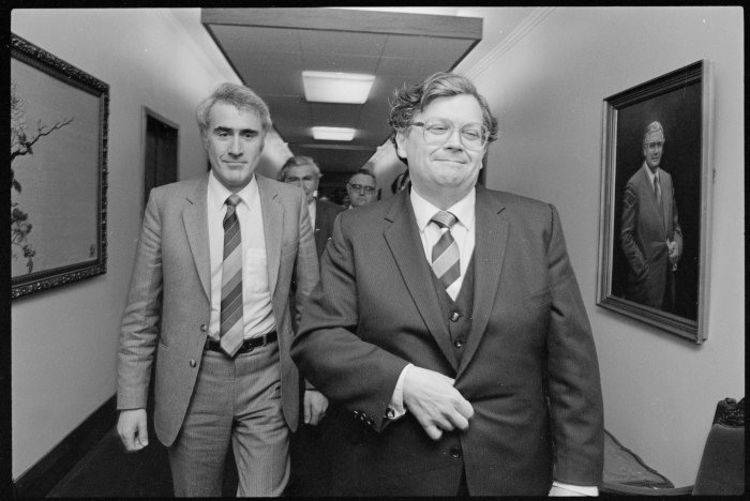

Prime Minister David Lange and Geoffrey Palmer leaving the Labour caucus after the election of the cabinet. Photo - Ross Giblin, National Library.

Foreign Minister Winston Peters says that process will remain a “signature theme” of the current government. “Most regrettably,” he says, “there is little sign that those states which possess nuclear weapons have any intention of reducing their arsenals – indeed the converse is the case.”

In particular, Mr Peters highlights the following challenges:

- Advocating for progress toward the entry-into-force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (it needs 50 ratifications to bring it into force). The Treaty is a landmark instrument that represents a significant step towards a nuclear weapon free world. New Zealand has recently ratified it and we’re now engaged in active outreach - especially in the Pacific.

- Continuing to play a leadership role in the agreements banning cluster munitions and regulating the arms trade, including by promoting wider adherence to these treaties, as well as trying to ensure better implementation of the Arms Trade Treaty in the Pacific.

- Working with other states to strengthen disciplines on the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, which cause major civilian casualties.

- Supporting international efforts for appropriate controls on the development and use of lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS, also termed “killer robots”).

For Mr Bolger, the best news of all will be the day when the major powers — he mentions France and Britain in particular — overshadow New Zealand in their desire to see a nuclear-free world. “Imagine the power of the symbolism and the reality if those two countries gave up their nuclear weapons.”

None of the political leaders see this as an imminent possibility. Quite the reverse. The modernization programmes under way in the nuclear arsenals of all the current nuclear weapon possessors have sparked fears of a new nuclear arms race.

Newly released information about the number of accidents and ‘near-misses’ over recent decades has deepened awareness of the extent of the risk associated with nuclear weapons – aside from the risk of actual nuclear conflict.

“And it’s not just their view, it’s a thought that is widely shared right now,” Dell Higgie, the Ministry’s Wellington-based Ambassador for Disarmament says of the ongoing apprehension.

Ms Higgie ticks off “some” of the reasons why there is greater risk of the use of nuclear weapons than at any point since the end of the Cold War: accident, misadventure, cyber attack or the attempts by some terrorist groups to acquire the weaponry.

“So yes, I think that our previous prime ministers are right in saying that the risk now is higher than it has been for some considerable time.

On the other hand, there have been triumphs along the way. “I don’t want to sound too much like a lawyer obsessed with treaties, but for me, the highlights of my decade doing this job have involved them,” she says, mentioning the Arms Trade Treaty and last year’s Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons — both of which New Zealand diplomats, with academic and political support, helped push through.

“The Prohibition Treaty builds on all those arguments put to the World Court by New Zealand and others over the decades. It follows the example of the treaties which have banned both the other types of weapon of mass destruction – chemical and biological weapons and for the first time, puts in place an explicit global prohibition on nuclear weapons. It’s not a king-hit, I know, given that none of the current nuclear weapon possessors seem likely to sign on to the new Treaty for the foreseeable future – and there are still those 15,000 or so weapons remaining. But it is nonetheless a very significant step forward”

Dell Higgie, the Ministry’s Wellington-based Ambassador for Disarmament

For as long as there is a possibility of nuclear war, however, the anti-nuclear battle remains.

“You either remain silent or you speak,” Mr Bolger, the politician turned diplomat, concludes. “And I always say you have to speak if something is wrong. If you don’t, who else is going to do it?”

Additional images

Image 1: Anti-Nuclear March held on Mothers Day. Christchurch City Libraries Flicker. File Reference: CCL-PCOL-AKS-056 From a private Collection. Collated for 2009 Beca Heritage Week’s ‘Doves & Defences’ - Discover Christchurch in Peace and Conflict.

Image 2: Anti-Nuclear protesters make their way through Akaroa 13 May 1984. Courtesy Kete Christchurch under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives 3.0 New Zealand License

Image 3: Demonstration against French nuclear testing, Princess Wharf. Credit Auckland Museum collection/Gil Hanly.

Image 4: CANWAR protesters on a yacht in Wellington Harbour, protesting against the entrance of American nuclear warships into Wellington. Credit National Library.