Primary Products:

On this page

Summary

- Japan fully relaxed its COVID-19 border restrictions on 11 October, one of the last major economies to do so.

- At the same time, Prime Minister Kishida announced plans to reinvigorate the tourism sector, hoping to maximise the benefits of the weak yen.

- Economists predict inbound tourist spending will only return gradually, and will not reach pre-COVID levels until 2025, due in part to China’s ongoing zero-COVID policy.

- Japan’s economy recovered to pre-COVID levels in Q2 2022, later than its peers did.

- Looking ahead, slow growth is forecast for 2022 (+1.7%) and 2023 (+1.6%).

- Inflation is still muted (2%), despite the weak yen affecting the price of imports.

- In a further attempt to further boost Japan’s economic growth and improve the equitable distribution of wealth, Kishida announced a “New Capitalism” economic stimulus package, including subsidies to support households struggling with high power prices.

- Despite Japan’s relatively slow recovery from the impacts of COVID, New Zealand’s goods exports to Japan were up +19% for the 12 months ending August 2022, to a record high of NZD 4.1 billion.

- This report includes an appendix outlining Kishida’s “New Capitalism” economic policy.

Report

On 11 October, Japan opened its borders to foreign tourists – reinstating visa-free travel from 68 countries (including New Zealand); removing pre-departure PCR testing for triple vaccinated; and lifting a 50,000-person daily cap on international arrivals.

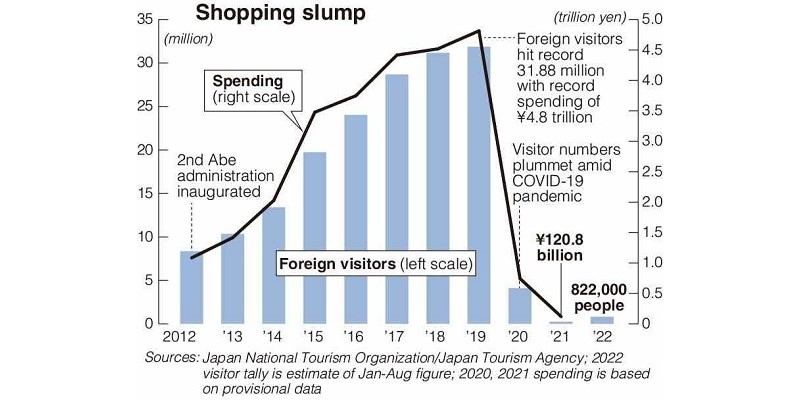

Under the second Abe administration (2012-2020), inbound tourism served as a key growth driver for the Japanese economy until Japan effectively closed its borders to foreign tourists in response to the spread of COVID-19 in April 2020. In 2019, a record 32 million overseas travellers visited Japan, spending 4.8 trillion yen (NZD $58 billion). Last year, this plummeted to 246,000 foreign visitors, spending 121 billion yen (NZD 1.4 billion).

Japan has been slower than many other countries to relax its border restrictions – with the United Nations World Tourism Organization(external link) (UNWTO) estimating that 86 countries had no COVID-19 related travel restrictions as of September 2022. As a result, while the number of international tourist arrivals (worldwide) has been steadily increasing since bottoming out in April 2021 (-86% on pre-COVID levels), Japan’s tourism slump and economic losses have continued. As of July 2022, the number of international tourist arrivals (worldwide) had recovered to -28% globally (compared to July 2019), with Europe at -16%, North America -26% and the Asia-Pacific region -75%. Japan lagged far behind the global and regional levels at -95%.

Kishida’s plans to reinvigorate the tourism sector

On 3 October, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida used his speech marking the start of an extraordinary Diet session to pledge to reinvigorate the tourism sector, and the broader economy, with the goal of increasing annual spending by overseas visitors to 5 trillion yen (NZD 60 billion). Kishida hopes the weak yen – which recently hit a 24-year low against the US dollar – will encourage foreign tourists (with their increased spending power) to return to Japan.

Kishida has also rolled out the “National Travel Discount” programme, providing a daily subsidy of up to 11,000 yen (NZD 132) per domestic traveller, which can be used for accommodation, meals, and shopping expenses. The new programme – replacing the “Go-To Travel” scheme – was initially planned to be introduced in July, but was postponed due to Japan’s seventh wave of infections.

Headwinds slowing tourism recovery

Despite Kishida’s ambitious goals, economists, such as Nomura Research Institute’s Takahide Kiuchi, and Japan Airlines (JAL) President Yuji Akasaka are predicting that inbound tourist spending will only return gradually, and will not reach pre-COVID levels until 2025. Japan’s tourism recovery faces significant headwinds:

- China’s continuing “zero-COVID” policy (China was Japan’s biggest source of tourists pre-COVID at 30%);

- US and European countries’ deteriorating economic outlook;

- High global energy costs keeping prices for long-haul flights elevated;

- Shortage of hospitality workers in Japan, with 73% of hotels reporting they were short of staff in August 2022 (up from 27% a year earlier);

- Lack of hotel rooms, with Japanese tourists still predominantly focused on domestic rather than international travel due to concerns about COVID-19 abroad.

Economy back to pre-COVID levels later than its peers – slow growth forecast

The Japanese economy recovered to its pre-COVID size in Q2 2022, with the relaxation of pandemic restrictions on businesses boosting consumer spending, which accounts for more than half of Japan’s economic output. While GDP growth for Q2 was +2.2%, the Japan Center for Economic Research reports that Japan’s GDP shrank 0.3% in August (month-on-month), as exports to the EU (-10%) and China (-8%) decreased – mainly due to a fall in electrical equipment and general machinery exports. The International Monetary Fund is projecting that Japan’s economy will grow by 1.7% this year and 1.6% in 2023. Japan’s recovery has been slower than the US and Europe’s, whose economies returned to pre-pandemic levels in Q3 2021 and Q4 2021, respectively.

Inflation still muted despite weak yen

While the weak yen supports inbound tourism (greater spending power), Japanese exports (cheaper prices abroad), and return on overseas investments (in yen terms), it increases the cost of imports – which is significant when Japan depends on imports for 90% of its energy needs. Higher costs for importing raw materials is also impacting on Japan’s manufacturing sector. The Bank of Japan’s quarterly business confidence survey indicates that sentiment among manufacturers, including the auto and electronic sectors, deteriorated for the third straight quarter in Q3 2022. This increase in energy and raw material costs was reflected in wholesale prices rising almost 10% in September 2022 year-on-year to their highest level ever. But Japan’s consumer price index – at 2% – remains lower than in other developed countries.

Kishida’s “New Capitalism” and his upcoming economic package to subsidise electricity prices

Since becoming Prime Minister in October 2021, Kishida has rebranded his economic policies from “Abenomics” to “New Capitalism”, a programme promoting both economic growth and redistribution of wealth (see Appendix for details). Kishida has signalled the government will release an economic stimulus package later this month consistent with his “New Capitalism” economic policy, and will table a second supplementary budget bill for this fiscal year (April 2022 – March 2023) during the current Diet session. As part of this package, Kishida has pledged greater incentives to encourage businesses to continue raising wages, and an “unprecedented measure” to directly support households and companies affected by increases in electricity prices.

According to media reporting, Komeito – the junior coalition partner – is seeking the inclusion in the stimulus package of 2 trillion yen (NZD 24 billion) for childcare support; and 500 billion yen (NZD 6 billion) for R&D on technologies relating to economic security. Media is also reporting that some lawmakers have floated a ballpark figure of around 30 trillion yen (NZD 356 billion) for the second supplementary budget.

Bilateral trade: New Zealand’s goods exports up 19% to a record high

Japan’s slow economic recovery has not negatively impacted bilateral goods trade with New Zealand. For the 12 months ending August 2022, New Zealand’s goods exports to Japan were up +19% yoy – the highest increase among our top five trading partners – to NZD 4.1 billion, a record high. Export growth was led by large increases by frozen beef (+80%), caseinates (+55%), aluminium (+42%), cheese (+26%), and wood chips (+29%). For the same period, New Zealand’s goods imports from Japan were up +26.5% yoy. For the month of August 2022, goods exports to Japan were up +16% to $313 million, led by rises in cheese (+148%), and meat and edible offal (+54%).

| Goods exports | Month of August | 12 months ended August | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | % | 2021 | 2022 | % | |

| $(million) | change | $(million) | change | |||

| China | 1,214 | 1,480 | +22.0% | 19,187 | 20,100 | +4.8% |

| Australia | 659 | 798 | +21.1% | 7,896 | 8,220 | +4.1% |

| USA | 559 | 656 | +17.5% | 6,419 | 7,367 | +15% |

| Japan | 270 | 311 | +15.3% | 3,406 | 4,055 | +19% |

| Rank | Industry | 12 months ending August 2022 (yoy) | ||

| $ Million | % Change | % Share | ||

| 1 | Dairy | 856 | +28% | 21% |

| 2 | Metal and Metal Products | 800 | +33% | 20% |

| 3 | Horticulture | 743 | -7% | 18% |

| 4 | Meat and Meat Products | 553 | +31% | 14% |

| 5 | Forestry and Wood Products | 398 | +19% | 10% |

| 6 | Miscellaneous F&B Products | 213 | +14% | 6% |

| 7 | Fisheries | 65 | +4% | 2% |

| Subtotal of leading industries | 3,627 | N/A | 90% | |

| Other goods | 428 | N/A | 10% | |

| Total | 4,055 | +19% | 100% | |

| Rank | Industry | 12 months ending August 2022 (yoy) | ||

| $ Million | % Change | % Share | ||

| 1 | Dairy | 856 | +28% | 21% |

| 2 | Metal and Metal Products | 800 | +33% | 20% |

| 3 | Horticulture | 743 | -7% | 18% |

| 4 | Meat and Meat Products | 553 | +31% | 14% |

| 5 | Forestry and Wood Products | 398 | +19% | 10% |

| 6 | Miscellaneous F&B Products | 213 | +14% | 6% |

| 7 | Fisheries | 65 | +4% | 2% |

| Subtotal of leading industries | 3,627 | N/A | 90% | |

| Other goods | 428 | N/A | 10% | |

| Total | 4,055 | +19% | 100% | |

Appendix

Economic Policy – Kishida’s “New Capitalism”

When Fumio Kishida became Prime Minister in October 2021, he rebranded “Abenomics” – the key economic policy of his two predecessors (Yoshihide Suga and Shinzo Abe) to “New Capitalism”, a programme promoting both economic growth and redistribution of wealth. Kishida has criticised Japan's neoliberal policies since the 1980s as having led to growing income inequality and poverty.

| Abenomics | New Capitalism |

|---|---|

| PM Abe (2021-20); PM Suga (2020-21) | PM Kishida (2021-present) |

|

Arrows:

|

Pillars:

|

| Goal: "Trickle-down effect" | Goal: "Virtuous cycle": growth and distribution |

Under the three arrows of “Abenomics”, Prime Ministers Abe and Suga asserted that increased profits of large corporates would “trickle down” to SMEs and the general public (which failed to materialise in practice). Under the four pillars of New Capitalism, Prime Minister Kishida argues that a distribution of wealth through increases in wages to expand the middle-class will invigorate consumption and lead to the next phase of Japan’s economic growth.

Pillar 1: People

The first pillar of New Capitalism is “investing in people” by increasing wages and asset-based income.

Kishida increased wages in the nursing and childcare sectors by 1-3%, and encouraged profitable companies to raise wages by 3%. This year’s wage negotiations led to an average of +2.1%, up from +1.8% last year. For SMEs, the wage increases were the highest since 2015. Unfortunately for the Kishida administration, these wage increases were overshadowed by high inflation (by Japanese standards) caused, in part, by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Kishida is reforming the tax system to encourage wage increases. For example, large companies are now allowed to deduct up to 30% of their wage hikes from their corporate tax bills (previously capped at 20%); with SMEs now allowed to deduct up to 40% (previously capped at 25%).

Under his “doubling asset-based income plan”, Kishida proposes mobilising assets currently sitting dormant in bank deposits towards investment to fuel corporate growth. For example, Kishida plans to expand NISA (Japan’s tax exemption program for small investments) and iDeCo (individually defined contribution pension plan). The plan has met with some criticism, as Kishida had initially campaigned on a promise of doubling “income”, not “asset-based income.”

Pillar 2: Investment in science, technology and innovation

Under the second pillar, the Kishida administration is increasing investment in science, technology and innovation, with quantum technologies, AI, biotechnology, digital, and decarbonisation being identified as priority areas. To boost investment, the government has launched a NZ$118 billion fund for R&D at universities.

Pillar 3: Start-ups

Under the third pillar, Kishida seeks to create a “start-up boom” in Japan. A work plan to foster a “start-up ecosystem” will be published by the end of the year, with the aim of a tenfold increase in the number of starts-ups over five years, to boost innovation.

Pillar 4: Green and digital initiatives

Kishida has re-committed to Japan’s target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 46% by 2030 and achieving net zero emissions by 2050 – arguing that green technologies could generate new economic growth. Japan’s reliance on coal and nuclear power will continue, with Kishida ruling out the possibility of entirely shifting to renewable energy. Kishida has promised to secure stable and low-cost energy supplies by maintaining various energy options, but Japan’s energy security risks have been exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and it remains to be seen how the invasion will affect Japan’s energy policy.

Whereas his predecessor Suga primarily focused on digitalising the government’s administrative systems, Kishida is focusing on digitalising regional areas as a way to revitalise the economy. This includes providing automated delivery services in remote areas, enabling remote medical care, promoting remote work and education, and subsidising agritech. As a first step, the government will be expanding 5G services and fibre optic networks across the entire country.

More reports

View full list of market reports

If you would like to request a topic for reporting please email exports@mfat.net

Sign up for email alerts

To get email alerts when new reports are published, go to our subscription page(external link)

Learn more about exporting to this market

New Zealand Trade & Enterprise’s comprehensive market guides(external link) cover export regulations, business culture, market-entry strategies and more.

Disclaimer

This information released in this report aligns with the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982. The opinions and analysis expressed in this report are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or official policy position of the New Zealand Government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the New Zealand Government take no responsibility for the accuracy of this report.