Supply Chains, Food and Beverage, Primary Products:

On this page

Summary

- Spain is a major food-producing nation both for Europe (where it grows one in four of the fruits and vegetables produced in the European Union) and internationally (traditionally producing more than half of the world’s olive oil, and 25% of the world’s citrus exports).

- Its current lengthy drought has put water reservoirs under strain and threatened primary production. Farmers refer to it as a “disaster”, and reduced food production is expected to impact food supply and prices within Europe and beyond.

- Droughts are common in the Mediterranean and the ongoing impacts of climate change mean that they are projected to intensify and lengthen. While short-term government measures have alleviated some of the impacts on growers in Spain, longer term solutions to water management in particular are required. There is scope for New Zealand agritech companies to engage with the world’s tenth largest agrifood producer on its challenges.

Report

Droughts are a frequent occurrence in Spain’s dry southern Mediterranean climate. The current drought, however, is particularly acute and prolonged – underway since the second half of 2022. The first four months of 2023 were the driest on record, with both April 2022 and then April 2023 breaking records for the warmest and driest months. The current low levels of surface and ground water have been compounded by years of drier-than-normal conditions, combined with a period of very low rainfall and high temperatures. Compounding droughts mean Spain is entering the summer with almost 20% less water stored in reservoirs than average. 40% of total Spanish territory is now in a state of drought, affecting 80% of farmlands. Spanish farmers and livestock owners talk about an “absolute catastrophe”.

Impact on primary production

Fruit crops through the south and east of the country are under threat. Wheat and barley harvests are “practically lost” in seven Spanish regions. There is so little water that it is expected that very little rice will be planted this year. Projections are that up to 50% of the olive oil harvest could be lost and a 50% reduction of almond production is expected, with water-intensive hazelnuts projected to see production drop by up to 90%. Beekeepers face a third consecutive season without harvest due to the lack of plant life. It is not yet harvest season for most fruits but they face an uncertain future with the current lack of water.

Last year, the wine sector advanced the grape harvest (the earliest ever) due to the high temperatures and lack of rainfall. Some wine producers note that 2022 was one of the lowest production harvests and expect an even smaller harvest this year.

Economic consequences and international impact

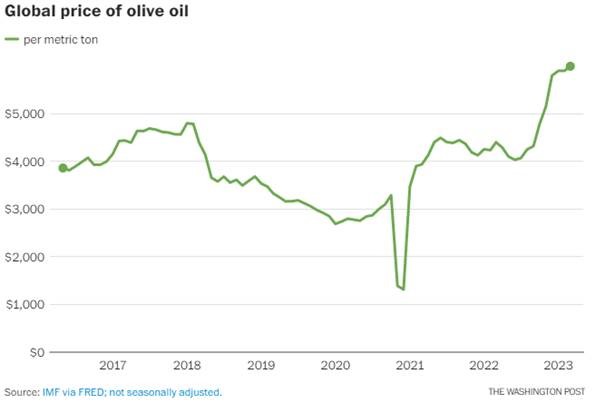

Following the well-documented impacts of Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, the drought is likely to keep food inflation higher, for longer. The price of olive oil – of which Spain has traditionally produced up to 57% of the world’s supply - is already the highest in history, as production declines (Spain produced only 680,000 tonnes(external link) from the 2022-2023 season, compared to nearly 1.5 million tonnes the previous year). In Spain, fresh fruit and vegetable prices have increased 5.6% and 15.6% respectively in the last year, and the forecast is that supply will be even lower this year, driving prices up further.

Spain, known as “Europe’s Orchard”, produces one third of the EU’s fruit production, and the EU is its primary market. It is responsible for 25% of the world’s citrus exports, of which 60% are oranges. A drought affecting Spanish food production is a cause of concern for other European countries and international markets for these products.

Germany, for example, is the largest market for Spanish fruit and vegetables within the EU. With a self-sufficiency rate of less than 40% for vegetables and around 20% for fruit, and limited potential to increase domestic production, Germany relies heavily on imports, in particular from Spain. Due to lower harvests, supply chain challenges and high inflation, German imports of fresh fruit and vegetables declined last year (respectively -7% and -14% in volume terms year on year), after many years of growth. This trend may well continue, as Spanish supplies in particular will be scarce and becoming more expensive. German consumers have proven to be highly sensitive to high food price inflation (still at 15% year on year in May), which is why demand could also continue to decrease as a result, despite growing interest in a healthy diet. The detrimental impact of intense freshwater use on Spanish conservation land has also been noticed in Germany, triggering a popular campaign urging German retailers to delist Spanish “drought strawberries”.

Like Germany, the UK relies heavily on food imports. Spain is its leading source of imported fresh produce, accounting for between 10-20% annually (and up to 80% of some salad and vegetable crops during the winter). In February, poor harvests in Spain contributed in part to high produce prices and product rationing by the UK’s major supermarket chains.

The Spanish drought is also having an impact on food supply and price in the Netherlands(external link), in particular where domestic production is not capable of replacing decreased Spanish supply. On the other hand, however, Dutch researchers note the impact of increasing investments in climate adaptation domestically. Growers are investing in irrigation and water retention through underground basins in order to use water more efficiently in times of drought. They argue this could increase the competitiveness of Dutch growers vis-à-vis those in the south. As climate change makes growing situations more difficult in the south, profits for growers in northern Europe may increase.

In adversity, opportunity?

The Spanish government has announced a range of measures to temporarily relieve the impacts of the drought. But the compounding nature of droughts, combined with the harsh and ongoing impacts of climate change, mean that longer term solutions are required. Changing environmental conditions may present opportunities for New Zealand businesses, specifically in the agritech sector. The fourth largest agrifood producer in Europe and tenth largest in the world, Spain is a major market for agricultural technology, specifically that which addresses irrigation and hot climate growing.

An increasing number of New Zealand companies recognise Spain as a priority market. Recent research commissioned by NZTE in Europe, shows that current European agri decision makers are looking to:

- modernise current systems; although Spain is a major grower, it is still traditional in its methods;

- increase crop yields and become more efficient (both indoor and outdoor growing);

- become more sustainable in their processes.

Droughts have been a constant in the history of Spain. Climate change will certainly exacerbate droughts in Spain and around the Mediterranean, making them longer, more intense, and more frequent. The primary sector will need to adapt to these new environmental realities, with water management as a top priority. Opportunity exists for New Zealand agritech companies to play a role in this development. Companies in the sector that have strong market awareness, and knowledge of the fragmented nature of the market and subsidy structure in Spain and Europe, will be the best equipped to thrive.

More reports

View full list of market reports(external link)

If you would like to request a topic for reporting please email exports@mfat.net

Sign up for email alerts

To get email alerts when new reports are published, go to our subscription page(external link)

Learn more about exporting to this market

New Zealand Trade & Enterprise’s comprehensive market guides(external link) cover export regulations, business culture, market-entry strategies and more.

Disclaimer

This information released in this report aligns with the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982. The opinions and analysis expressed in this report are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or official policy position of the New Zealand Government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the New Zealand Government take no responsibility for the accuracy of this report.