Supply Chains:

On this page

Summary

- Global shipping rates have nearly doubled since late April, but fortunately remain far below the peak reached during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The main reason is the current disruption in the Red Sea, which has stretched global shipping capacity, with more shipping needed to service European and Asian routes. Since December, there has been a 50% fall in shipping traffic navigating the Suez Canal, offset by a 70% jump in sailings around the less direct Cape of Good Hope.

- Adding to disruptions is a shortage of shipping containers and congestion at some major Asian ports. At the same time, global export demand is recovering following a muted post-COVID lull in 2023. As a result, the WTO is expecting a 2.6% increase in goods exports in 2024, following a slight decline last year.

- The rising cost of doing trade, if it worsens, poses a risk to Kiwi consumers and businesses already facing challenging economic conditions. Interest rates remain high, firms’ margins are under pressure, and unemployment is rising in New Zealand. A sustained rise in shipping costs could complicate the Reserve Bank’s task of getting inflation back to within its 1-3% target band.

- Fortunately, the current rise in shipping costs is likely to be less inflationary than the surge experienced during COVID. Rising shipping costs this time around are less widespread, container production is ramping up, and disruptions in the Panama Canal – another current chokepoint – are easing.

- However, and more importantly, the softer economic conditions here at home mean firms have less scope to pass shipping cost increases on to consumers.

Report

Global shipping costs, particularly the cost of servicing European markets, are once again on the rise. As shipping companies continue to avoid the Red Sea, seaborne freight capacity has become finely balanced, making freight prices more responsive to shifts in the market. And shipping costs are currently responding to a recovery in global trade, a shortage of containers, and congestion at some major ports. These current developments have raised concerns of disruptions to New Zealand’s trade flows and upside risks to inflation. However, as explained below, there are reasons to believe that the current jump in shipping costs may prove more transitory in nature and have less impact on inflation than experienced during COVID.

The threat of attacks by Houthi rebels in the Red Sea continues to weigh on global shipping...

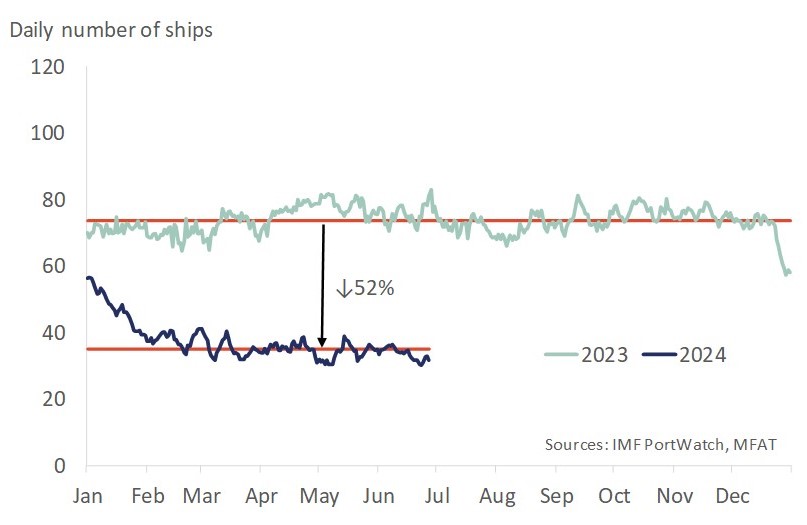

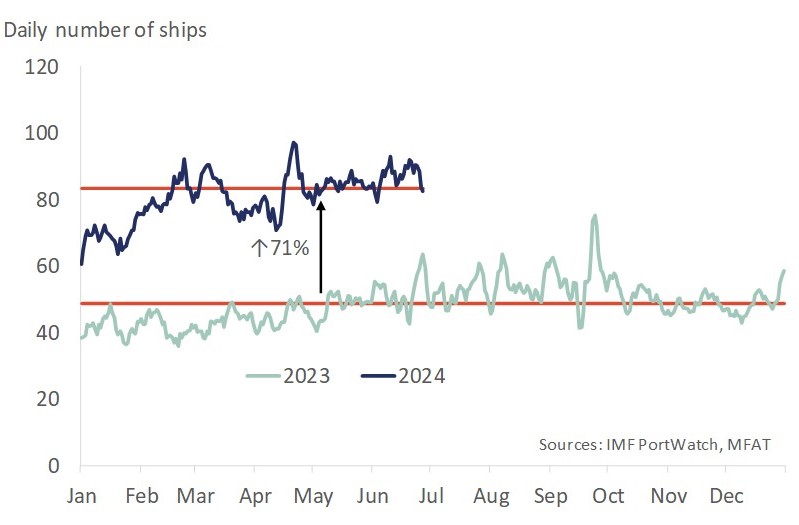

In the opening months of 2024, commercial shipping between Asia and Europe faced significant disruption in the Red Sea because of Houthi attacks on vessels transiting the area. For the most part, commercial shipping companies decided to divert shipping away from the most direct route, via the Suez Canal, and instead sail around the African continent. Data from IMF’s PortWatch reveals that since December last year sailings of commercial shipping via the Suez Canal fell by around 40 per day or 52% (Figure 1a). At the same time daily sailings around the Cape of Good Hope gained an average 35 sailings or 71% (Figure 1b). The move added around 40% in voyage distance, causing shipping delays of 2-5 weeks, and raising costs of trade to and from Europe.

Figure 1: Commercial shipping continues to avoid the Red Sea

Further adding to global shipping woes, the Panama Canal, another key trade route between the Indo-Pacific and Europe, was also adding to the disruption of global seaborne trade. Low water levels caused by to an extended period of drought last year forced operators to place restrictions on the number of ships transiting the waterway and draft limits that reduced the weight these ships can carry.

…propelling shipping costs higher once again and posing a risk to Kiwi households and firms.

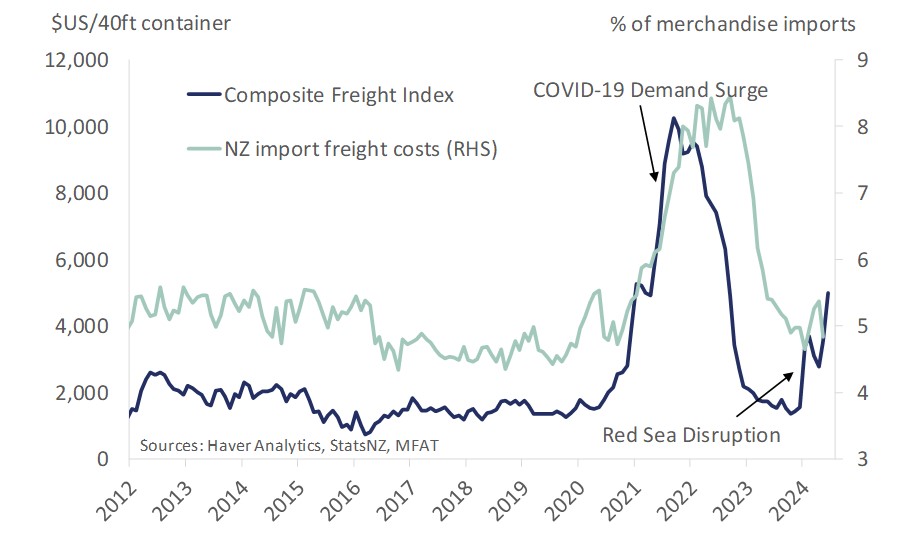

After an initial jump in freight rates in January, shipping costs began to moderate as global supply chains adjusted to a new reality. Since May however, we have seen the resumption of rising freight costs. Global measures of shipping rates have almost doubled since late April (see Figure 2 below). And on some routes, such as Shanghai to Rotterdam, costs have experienced much larger gains. Fortunately, overall shipping costs still sit well below the peak experienced during COVID-19. However, it will take time to show up in New Zealand economic data, with shipping costs typically being recorded with a lag of around 3-to-9-months (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rising shipping costs take time to be felt in New Zealand*

Nevertheless, the current rise in the cost of doing trade poses a risk to Kiwi consumers and businesses facing challenging economic conditions. Rising shipping costs, if they are sustained, could place additional upward pressure on the prices of the imported products that businesses need to operate, and households need to live. Moreover, there is a risk that rising import prices could delay the return of inflation back to within the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s (RBNZ) 1%-3% inflation target band. The RBNZ may then need to keep interest rates higher for longer, heaping further pressure on New Zealand households and businesses.

Global sea freight capacity has become increasingly stretched, making prices more sensitive to a recovery in global exports...

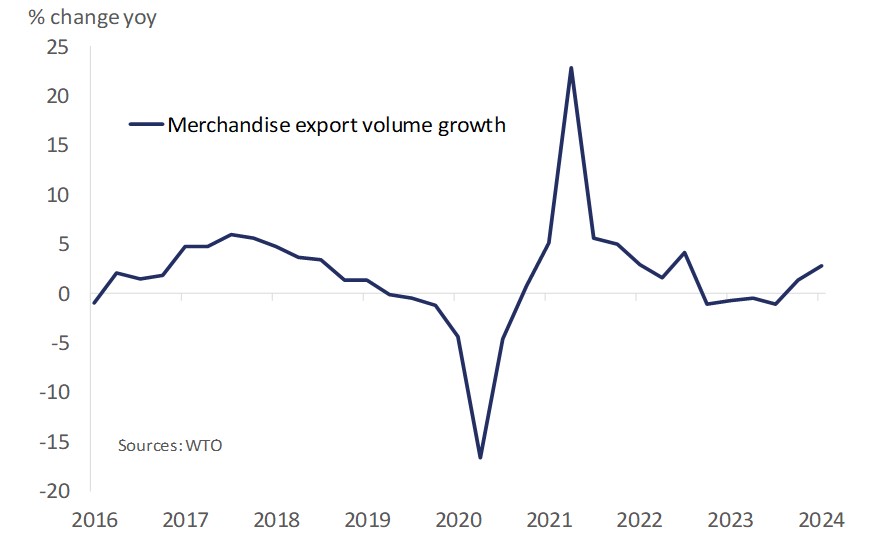

Current shipping disruptions have led global shipping capacity to become finely balanced, meaning prices are more sensitive to changes in demand. Shipping capacity has been taken up because longer sailing times between Asia and Europe mean more ships are needed to service these routes. At the same time global merchandise export volumes are recovering (Figure 3), and particularly those from Asia. For example, China’s goods exports have shown strong growth over the first half of 2024 and even posting a 7.6% yoy jump in May. A resilient US economy has supported demand, but there has also been a general rebuilding of inventories globally. Global trade is expected to recover further over 2024, with the WTO forecasting the volume of global merchandise exports will expand 2.6% this year, following a small contraction last year.

Figure 3: Global export growth is recovering after a subdued 2023

…and a shortage of shipping equipment such as containers.

Another consequence of ongoing disruption has been a shortage of shipping equipment, especially containers. With ships spending more time in transit, the global shipping sector requires more equipment to transport goods to and from Europe. Moreover, the net flow of containers tends to be from China, as a major global manufacturer, towards consumers in the West. Currently empty containers aren’t returning to where they are needed quickly enough, adding to the equipment shortages. Some shipping companies are having to unload and sail without empty containers to meet schedules. In addition, new container production dropped off sharply last year, as merchandise trade experienced a post COVID fall. The shortage has seen the price of containers rise sharply, with containers in China doubling in price compared to September.

The rerouting of ships around Africa and shortages of equipment are causing flow-on effects, including an increase in off-schedule arrivals that is playing havoc with logistics management and increasing congestion at some major Asian ports. Ships calling on key Asian ports, such as Singapore and Shanghai, are experiencing delays in entering ports and in the loading and unloading of cargo. These ports are also vital for New Zealand exports to Asia and beyond.

Encouragingly, the current bout of rising shipping costs on inflation looks likely to be less severe and more short-lived than the experience during COVID-19

While shipping costs are likely to remain elevated while commercial shipping avoids the Red Sea, current supply-chain issues are not expected to match those experienced during the pandemic disruption. Firstly, the rise in shipping costs this year have not been experienced universally and have been most acute on routes between Asia and Europe. In contrast, the COVID-19-driven surge in shipping costs was felt worldwide, resulting from a policy-stimulated explosion in the demand for goods in 2021.

Secondly, manufacturers are already responding to the shortage of containers by boosting production. China is the largest manufacturer of shipping containers and production has been ramping up. According to Bloomberg(external link), over the first five months of this year manufacturers in China have produced a similar number of new containers as they did over the same period in 2021. As the new supply of containers come online, they should help to plug some of the gaps experienced by shipping companies.

Thirdly, conditions in the Panama Canal are improving and allowing authorities to begin easing restrictions there. Water levels in Lake Gatun, the main body of water that feeds the canal system, have been steadily rising since April. And above-average rainfall forecasts have allowed canal authorities to increase the number of ships able to ply the waterway. From late July, 34 ships per day will be able traverse the canal, up from 24 at the start of 2024 and not far from 36-38 ships per day typical under normal conditions. Authorities have also relaxed draft limits on vessels, allowing ships to carry larger loads though the waterway. Although the Panama Canal is a far smaller chokepoint than the Suez Canal, accounting for around 7% of global seaborne trade, improved conditions should take some pressure off global shipping.

Finally, the economic climate both here in Aotearoa and abroad is vastly different to what was experienced during the pandemic. For instance, the sustained rise in inflation during the COVID-19 pandemic was driven by a global surge in demand that was broad based across goods, labour, and capital markets. In contrast, current global shipping disruption is an isolated supply-side inflation factor. At the same time demand is far more subdued with households tightening their belts in the face of high interest rates and rising unemployment. However, this also means that New Zealand firms have less scope to pass shipping costs on to consumers this time around potentially squeezing margins further. The consensus among local forecasters is that inflation is still on track to return to within the RBNZ’s target band in the second half of this year. For now, rising shipping costs remain a risk factor in the fight against inflation.

Shipping is vital for New Zealand’s merchandise trade. Not just to export our key commodities around the world, but also to access vital inputs for domestic economic activity. Global shipping costs are likely to remain elevated so long as the threat of Houthi attacks in the Red Sea keeps commercial shipping from using the Suez Canal to move goods to and from Europe. Excess sea-freight costs are a drain on the economy, especially at a time when New Zealand firms and households face challenging economic conditions. Fortunately, the current episode is likely to be less severe than the experience during COVID-19.

More reports

View full list of market reports

If you would like to request a topic for reporting please email exports@mfat.net

Sign up for email alerts

To get email alerts when new reports are published, go to our subscription page(external link)

Learn more about exporting to this market

New Zealand Trade & Enterprise’s comprehensive market guides(external link) export regulations, business culture, market-entry strategies and more.

Disclaimer

This information released in this report aligns with the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982. The opinions and analysis expressed in this report are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or official policy position of the New Zealand Government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the New Zealand Government take no responsibility for the accuracy of this report.