Food and Beverage, Primary Products:

On this page

Prepared by the New Zealand Embassy in Brussels.

Information in this report is sourced either via public resources or from conversations with contacts.

Summary

COVID-19 had a range of impacts on EU agricultural markets. The largest immediate effect was on the demand side as the hotel, restaurant and café sector was essentially shutdown overnight. Products largely destined for that sector could often not be directed elsewhere and in some cases, e.g. cut flowers, a large proportion of production had to be destroyed. On the supply side the agriculture sector showed resilience. There were very few and only short-term shortages of products in supermarkets, and the initial logistical difficulties as some borders closed were quickly resolved through the creation of green lanes for the movement of agricultural products. Having said that, restrictions on the movement of agricultural workers had a negative effect on the production of some horticultural crops and meat. While progress has been made allowing agricultural workers to move between countries there are still shortages in some areas and COVID-19 out-breaks in some horticulture and meat production facilities, often resulting from poor working and housing conditions for migrant workers, have also affected production. These issues could spill over to the next production season to some extent. Overall the situation has stabilised in the EU, but risks remain, especially as COVID-19 infection rates start to increase again in many countries. The following paragraphs summarise the impacts on some important sectors for New Zealand.

Report

Dairy

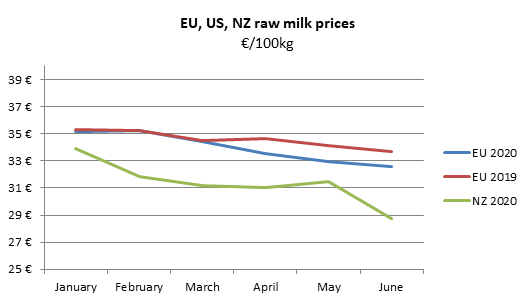

The EU farm-gate price for raw milk started the year strong at €35.2 per 100kg, following a similar track to 2019. In the first two months of the year, when the pandemic was escalating in China and Wuhan remained under lockdown, EU industry reported minimal issues with production, exports remained stable, and prices held. However there were some challenges with exports to China, primarily due to lockdown restrictions, and also some physical supply chain issues, but the impact of these issues on prices did not materialise immediately.

By March COVID-19 was well and truly established in the EU, and many European countries had entered into highly restrictive lockdowns. Certain member states and/or regions began experiencing production issues as a result of labour shortages which were caused by border restrictions, and in some cases as a result of sickness related to the virus (e.g. Parmigiano Reggiano production in Northern Italy), but these were not large scale and were resolved relatively quickly. The closure of the food service sector led to increased demand for retail products, with producers switching, where possible, towards producing more retail products (e.g. butter, yoghurts, creams and consumer cheeses) as well as lower risk long-life products (such as skim milk powder) in anticipation of government support measures. EU industry says that increased sales into retail channels did not make up for the losses experienced in the food service sector, and that these changes in market dynamics coupled with uncertainty led to a decrease in prices. Within the overall situation, the fortunes of individual companies varied significantly with companies with less ability to adjust their product mix often severely affected, although most were able to use economy-wide support schemes to remain in operation.

COVID-19 came at a time when EU milk production was entering its seasonal peak (around April). There was initially concern that higher than expected milk supply would add further downward pressure on prices, but efforts to curb milk supply volumes in some countries (e.g. by paying for voluntary reduction) and drought in parts of Europe improved market sentiment. The European Commission announcement of support for the sector in the form of private storage aid (which has now ended) was also a factor. That said, overall milk supply still increased by 2% from January – May, led by strong growth in Italy, Poland, Germany, Netherlands and Ireland, and the Commission expects milk supply for the year to be up 0.7% on 2019 as feed prices are expected to remain low.

Consumer demand also stabilised, and strong price decreases were not sustained in the EU. The Commission has reported that the EU milk price dropped only €40c in May, and €35c in June, compared with larger decreases in February/March. This remains a milk price that would be above breakeven for most European farmers. Figure 2 below, shows the impact of these market dynamics on the prices for butter, skim milk powder (SMP), whole milk powder (WMP) and cheddar, which are all showing signs of recovery.

While things are looking relatively stable for the dairy sector, European industry groups remain concerned about uncertainty and are asking the Commission to remain ready to support the sector if necessary.

Meat

Beef

The closure of the food service sector in Europe hit the beef sector hard. High value cuts of meat temporarily lost their main sales outlets, with demand for veal particularly impacted as this product is eaten almost exclusively in restaurants. Demand increased for low value products like mincemeat as consumers cooked more for themselves, however this was unable to compensate for the drop in demand for these products due to the closure of fast food restaurants. February, March and April therefore saw prices dip steeply in comparison to the previous year, as shown in figure 3.

By May many EU countries had started to ease restrictions on the food service sector and prices have now somewhat stabilised albeit below 2019 values. The European Commission is predicting a 1.7% decline in EU beef production and a 2.7% reduction in consumption (taking into account restaurant closures) this year.

Despite these domestic difficulties, EU beef exports climbed 4% in Q1 of this year and are expected to increase by 2% overall in 2020 as China continues to be an attractive market in the midst of its ASF crisis and subsequent protein shortage. Imports, on the other hand, were down 17% in Q1. The reduction in imports mostly came from the UK and Mercosur countries. Imports of New Zealand beef into the EU (frozen and chilled) during the first six months of the year were down by 5.3 % when compared with the first six months of 2019 (from 2369 tonnes to 2244 tonnes) and were worth €20.9 million (a 17.2% decrease in value). Imports of New Zealand beef (frozen and chilled) into the UK were down 64% during the same period (from 262.2 tonnes to 94.6 tonnes) and were worth €496,000 (a 52% decrease in value).

As the pandemic continues in Europe, there have also been production issues for slaughterhouses - notably in Ireland and Germany, where COVID-19 infection clusters have caused the closure or slow-down of processing. The clusters have been blamed on poor working and living conditions, usually for migrant workers.

Sheep meat

EU sheep meat prices fluctuated in the first half of this year with light lamb in particular showing a steep drop both due to COVID-19 measures and increased uncertainty due to Brexit. Despite the variation prices have not fallen lower than in the same timeframe in the previous year, and prices are recovering as the food service sector reopens.

The European Commission now expects sheep and goat meat production to decline by 1.5% this year (its previous forecast had production stable), as producers take into account the decline in demand which stemmed from reduced foodservice as well as reduced home consumption (including the effect of lockdowns on Easter and Ramadan celebrations) as well as COVID-related logistical issues causing supply shortages. While previously the Commission had predicted sheep meat consumption to fall by 0.4% in 2020, it is now predicting a 3% decline as a result of COVID-19.

Supply is tight in the EU, but exports of sheep meat were up 9% on the same period in 2019 due to strong demand in key markets such as Switzerland, Oman, UAE, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia which more than made up for the loss of sales to the UK (-15%). The EU exports about 10% of its production. Export growth is expected to soften later in the year as global supply tightens even further.

Total imports to the EU, however, were down significantly during the first six months of the year falling by 21.3% (from 77,161 tonnes to 60,747 tonnes) and were worth €460 million (a 16.4% decrease in value). Imports of sheepmeat from New Zealand for the equivalent period were also down by 16% when compared with the first six months of 2019 (from 34,227 tonnes to 28,719 tonnes) and were worth €255 illion (a 13.6% decrease in value). Imports of sheep meat from New Zealand into the UK decreased by 7.2% from 25,657 tonnes to 23,797 tonnes and were worth €156 million (a 1% decrease in value).

Brief glance at other meat categories

As different meats often act as substitutes on the market it’s interesting to take a look at what happened to the poultry and pork industries.

As consumers increasingly cooked at home during restrictive European lockdowns one might have expected to see consumers switching from sheep and beef towards chicken. However the spread of avian influenza in Poland, a major European producer, coupled with the strong reduction in food service (where between 20-40% of EU poultry is consumed) lead to an overall reduction in demand and prices. EU consumption of chicken is expected to drop 2% this year as a result of food service closures.

Prices for pig meat started the year exceptionally high following a surge in global demand in 2019 related to ASF, but plummeted with food service sector closures back towards their 5 year average. With demand out of China not slowing down, the sector remains optimistic and the Commission predicts production to be strong in those EU countries less affected by ASF. Production in Poland and Italy however, has dropped sharply. Exports of pig meat are strong (exports to China have apparently grown 150% but are expected to soften in the second half of the year), while EU chicken exports have decreased (by 8% in Q1, and it also expected the overall reduction in exports will be 8% for 2020).

Wine

The EU wine industry has been highly vocal about the strife COVID-19 has caused the sector. Earlier this year when full lockdowns were in place some activities in cellars were stopped as a result of the implementation of health measures. The sector also noted reduced availability of glass bottles due to a reduction in activity from suppliers (up to 50% in some cases), and reduced availability of truck drivers. According to Comité Vins (the representative body for EU industry and trade in wines) some producers experienced a rise in transport costs of anywhere between 30% and 70%.

With the closure of bars, restaurants and hotels the wine sector lost a significant proportion of its “on-trade” distribution channels. Just how much is sold through on-trade channels differs by country, but ranges from 72% in Austria and 67% of sales value in France, and 64% in Spain, down to 26% of sales value in Romania and 41% in Germany, for example. Countries where tourism plays a big role in the economy tend to be more strongly affected, while many companies who specifically directed sales towards on-trade channels stopped trading all together. Comité Vins estimate that 30% of total production was impacted by the closure of on-trade channels and around 50% of the value.

Off-trade channels, such as supermarkets, largely remained open, however a portion of this was also lost due to the closure of duty-free stores and lack of travel (especially relevant for categories such as Champagne). Wine sales in supermarkets increased by around 20% in the first half of March, however they dropped in the second half. Interestingly bag-in-box wine sales increased by 40% over the same period in 2019. Online sales were more popular than ever with most e-platforms registering between 60% and 100% increase in sales volume, and a 10% increase in sales frequency. However this growth started from a low base and did not compensate much for the drop in on-trade sales.

The European Commission predicts EU wine consumption to drop by 7% in 2019/2020 due to COVID-19 related changes in consumption patterns, while vinified production for other uses (e.g. distillation, vinegars, brandies) is expected to increase significantly as producers try to manage oversupply. In 2019 wine stocks reached a 10 year high of 178,337,000 hL and could increase significantly this year putting pressure on prices. Increases in distillation and green harvesting are possible due to exceptional measures introduced by the European Commission to support the sector. The Commission expects a reduction in total wine production of 4%.

EU wine exports are expected to decline by 6% this year in comparison to the 5 year average, while at the same time imports could decline by 13%. In January-April, exports to China fell by 18% compared to the same period last year, whereas exports to the US only decreased by 3% despite additional import duties. Comité Vins reported that almost 100% of wine operators had been unable to maintain their exports as the same level since the crisis had started.

As you can see from the French and Spanish wine prices in the charts below most wine categories have experienced price declines since January. The Spanish figures extend to July, where we are able to see that with the reopening of the food service sector over the European summer has helped some wine categories begin to recover.

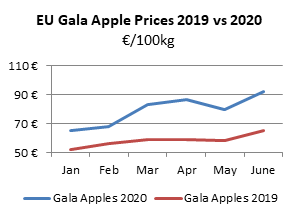

Fruit

Demand for fresh fruit which lasts well skyrocketed in the EU as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns. This meant that fruit such as apples, oranges and kiwifruit did particularly well, especially as consumers more consciously chose foods high in nutrients like vitamin C. EU demand for fresh apples is predicted to be 9% higher than average.

Apple prices in Poland (25% of EU production) were particularly high, also as a result of low stocks and low expected production in 2020 due to frosts in April/May. (In figure 11 week 25 refers to the week ended 21 June 2020).

On the flipside demand for tropical fruits is down, likely due to air-cargo constraints being felt globally, which may be contributing to the increased demand for apples and other staple fruits.

EU exports of fresh apples fell by 32% over January-April compared to the same period last year due to increased EU demand, lower production, and the difficulties to reach some export markets (e.g. India) due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Potatoes

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on the EU potato market. French fries was one of the food categories most severely impacted by food service closures across the continent. As a result, demand for potatoes dropped, a development that was reflected in the evolution of potato prices. April 2020 saw an 83.8% drop in prices compared with April 2019. While prices picked-up gradually in May, as lock-down measures started to ease, prices in June 2020 were still 35% lower than prices in June 2019.

During the first six months of the year EU exports of preserved or prepared potatoes (including French fries) declined by 12.8% when compared with the first six months of 2019 (from 1.3 million tonnes to 1.1 million tonnes) and by 18% in value from €999m to €819m. During the same period exports of potato preparations from the EU to New Zealand grew by 3.2% (from 2427 tonnes to 2506 tonnes) and by 17.4% in value, from €2.1m to €2.5m.

To contact our Export Helpdesk

- Email: exports@mfat.net

- Phone: 0800 824 605

- Visit Tradebarriers.govt.nz(external link)(external link)

Disclaimer

This information released in this report aligns with the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982. The opinions and analysis expressed in this report are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or official policy position of the New Zealand Government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the New Zealand Government take no responsibility for the accuracy of this report.