Ministry Statements & Speeches:

Public Lecture: Sea-Level Rise and International Law

Victoria Hallum, Chief International Legal Adviser, MFAT

The theme of this year’s Beeby Colloquium, of which this public session is a part, is “International Law: Seismic Shifts and Fracture Points”. We intended this as a metaphor to capture the turbulence and tensions that are shaking the rules-based international order at present.

Looking at the topic of this session, “Sea Level Rise and International Law”, however, we can see there are physical not just metaphorical forces at play and we are experiencing a literal shift affecting the surface of our planet (albeit of course a human induced one).

Bruce Burson has laid out the human mobility and human rights issues associated with sea-level rise. I now want to talk about what the law of the sea issues are, why they are so important and what New Zealand is seeking to achieve in this area.

Simply put, the key law of the sea “problem” caused by sea-level rise is the “shrinking” or “shifting” of states’ maritime zones and the associated resource rights that are part and parcel of these zones.

While at first glance this may not appear to have the same human face as the matters discussed by Bruce, in reality we are talking about people’s livelihoods and resources that are critical for the sustainable development of entire countries. And beyond the economics, this issue also raises some crucial questions about equity and fairness at international law.

To appreciate the law of the sea issues at play, you need to generally understand how maritime spaces are measured under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (or “UNCLOS”). I will explain this briefly for those who are not familiar with the subject.

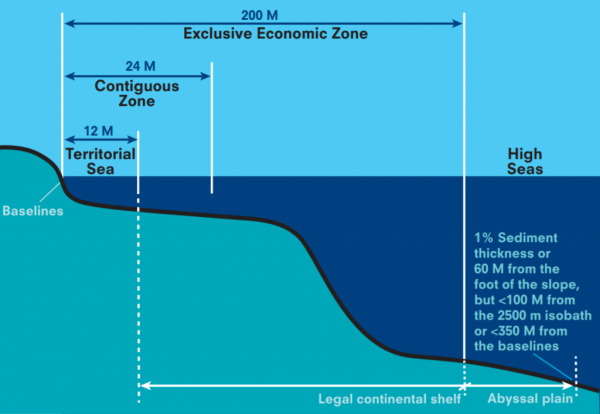

As you can see from the diagram, maritime zones are measured from baselines. As a general rule baselines follow the low water line around the coast. There are exceptions to the low water line “rule”, for instance: straight baselines to accommodate heavily indented coastlines, archipelagic baselines and special formulas for dealing with bays. But I won’t go into those details today.

As you can also see, the territorial sea, contiguous zone and exclusive economic zone are all measured from these baselines.

Inhabitable outlying islands can also generate their own maritime zones, which are also measured from the baselines on the coast of those islands.

The position of a state’s baselines affects the position of the outer limits of its maritime zones. The general consensus, reiterated by the International Law Association, is that these baselines are “ambulatory” – which means that despite being set on maritime charts the baselines will move if the coastline changes. It is the actual water line that matters, not what is marked on a chart.

If sea levels rise and the low water line moves inward, then the baseline and the outer limits of the EEZ will also move towards the land. States affected by sea-level rise will experience a shrinking or shifting of their maritime zones as the low-water line gradually creeps inland, and the outer limits of states’ maritime zones follow. Some outlying islands that generate maritime zones may disappear altogether.

So there we have the problem.

As a result, what was originally within a state’s EEZ will become high seas. Waters where the coastal state once had sovereign resource rights, including over fisheries, become part of the high seas and the coastal state immediately has far fewer rights.

The impact of this will vary considerably and will clearly be much greater in low lying land territories than countries with big sea cliffs.

For low lying countries the loss or even uncertainty over their rights is likely to be really significant, particularly for countries that are heavily reliant on the marine resources in their EEZs for economic development.

You may find this all interesting, but wonder why – given we are not a low-lying island – the New Zealand Government is so engaged in the international legal complexities of the issue.

There are three main reasons:

- First, this issue impacts the people of the Pacific; our neighbourhood. The Government has publicly committed to leadership on climate change, including taking early and collaborative action on climate-change related displacement and migration. New Zealand’s approach to this is underpinned by respect for Pacific Island countries’ sovereignty and the right to self-determination. The international legal aspects of sea-level rise have a key role to play in this.

- Second, New Zealand remains a strong supporter of the rules-based international order in general and UNCLOS in particular. We have been a long-term and strong supporter of UNCLOS and during the negotiations New Zealand was particularly active in securing coastal State rights, including those of small island states. New Zealand does not want to see these hard-won rights whittled away by climate change.

- Third, there is a fundamental issue of fairness and equity at play. In the last thirty years, relying on rights confirmed by UNCLOS, small island states have developed resources in their ocean spaces (particularly fisheries) as a crucial pathway to sustainable development. It is inequitable that they may now see those rights and resources eroded because of a phenomenon they have done the least to cause, and which the drafters of UNCLOS never foresaw.

New Zealand has said publicly that it wants to work with partners to preserve the current balance of rights and obligations under UNCLOS. Our goal is to find a way, as quickly as possible, to provide certainty to vulnerable coastal states that they will not lose rights over their marine resources or maritime zones due to rising sea-levels. We want to start a conversation about this and listen to other perspectives, in the Pacific and further afield.

New Zealand is certainly not alone in this endeavour. Our partners in the Pacific have been actively pushing these concerns for some time. As Dame Meg Taylor, Secretary-General of the Pacific Islands Forum has said, settled maritime boundaries provide certainty about the ownership of our ocean space, which is vital for managing our oceans resources, biodiversity, ecosystems and fighting the impacts of climate change. Australia, for its part, has a long running project to assist Pacific Island countries in fixing their baselines which is an essential first step.

Fortunately there is a growing awareness and concern about this issue in the international community. I was pleased when I was recently in New York at International Law Week as part of UNGA to hear how much support there was for the International Law Commission taking up the subject of Sea Level Rise in International Law.

While we think the ILC has a valuable role to play, we don’t think this is sufficient on its own. We think that states need to work in parallel with the ILC. This is an exciting opportunity for New Zealand to work with other states to try to address a “real world” issue through international law.

So now you know the contours of the problem and why it is so important, I now wish to look at what might be able to be done about it.

The International Law Association has been working on this issue for a number of years, and it has considered various solutions to the law of the sea issues involved. In its most recent report the ILA recommended that once baselines and maritime zones have been established consistently with UNCLOS, these should be permanently “fixed”, thus eliminating any requirement to recalculate maritime limits in light of subsequent sea level rise. This may well be the clearest and cleanest solution to the problem.

This approach would allow states to retain their existing maritime entitlements established in accordance with UNCLOS. It would also avoid inequity and remove uncertainty about whether a state’s maritime boundaries may have shifted.

As the ILA set out in its resolution, this approach can only apply where the existing maritime entitlements have been established in accordance with UNCLOS, which is why the Australian-supported work on establishing maritime boundaries is so important.

The real question for us, as practitioners of international law, is how – practically – we can develop the law in that direction.

There are various options that can be explored. They range from legally binding options – negotiating an amendment to UNCLOS or a new implementing agreement; to resolutions by the General Assembly or States Parties, to advisory opinions or even unilateral actions.

The various options are more or less legally persuasive, and more or less achievable. As is often the case, the most legally robust option, is the most difficult to achieve; and the most achievable option is the least legally robust.

The first and most obvious option is amending UNCLOS to make it clear that once baselines and the limits of maritime zones are established in accordance with the Convention they do not change. One could imagine a relatively simple amendment that would achieve this outcome.

While the process for amending the Convention is notoriously difficult (unless of course you managed to satisfy article 313’s simplified process) in reality it is not the procedural hurdles that will be the main obstacle. The Convention took 20 years to negotiate and enter into force and is finely balanced package of rights and obligations. While many countries may agree that low-lying islands losing maritime space from sea-level rise is a perverse consequence that the drafters of UNCLOS did not intend, we think very few countries would risk re-opening the UNCLOS package. The risk of other amendment proposals coming out of the woodwork would simply be too great for many states to entertain.

In light of this, any solution is likely to require a more creative and incremental approach, focused on consensus-building over time. A softer law step may need to be the starting point.

Potential options

Global option

UNCLOS States Parties resolution

UN General Assembly resolution

Interpretative guidelines or understanding of the Parties

Declaration or pledging conference

International Law Commission guidelines or draft articles

Advisory opinion from ITLOS

Regional options

Decisions by regional sectoral organisations (e.g.: RFMOs)

Regional statements or actions.

Unilateral statements or actions

Have a role in building state practice but global adherence will be key.

As you can see from above, there are a range of possible options which fall short of amending the Convention. A resolution of the meeting of States Parties to the Convention specifying that a state’s baselines and limits of its maritime zones are not required to be recalculated due to sea level rise is an option worthy of consideration.

Depending on its content, such a resolution could be considered a subsequent agreement of States Parties which could, according to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, be taken into account when interpreting the Convention.

While a potentially elegant solution that would reduce the risk of “re-opening” the Convention more generally, it would not be without risk nor as easy to sell to other States Parties as you might imagine.

This is because there is a tradition in the meetings of States Parties to the Convention to not deal with any substantive or contentious issues, preferring instead to focus on the more administrative issues (such as the election of ITLOS judges, report back from bodies created by the Convention, agreeing budgets etc). While the States Parties have adopted resolutions in the past that have interpreted the Convention, these have all been procedural.

Our sense at this stage is that while many states would be comfortable in substance with what we want to achieve, they may still resist it because – and here’s that floodgates argument again – if the meeting addresses one substantive issue, why not others? While this does not mean a resolution of the States Parties is impossible, it may suggest other steps could be worth taking first (for example, adding language in a UN General Assembly resolution or a declaration by a cross-regional group of countries).

Before wrapping up and allowing some time for discussion, I wanted to note that while I have talked mainly about the global level there are regional options that may be worth considering. Decisions of competent regional bodies could be useful indicators of state practice. While a regional decision would not bind third states, if it was a decision of a regional fisheries organisation, it could at least assist in protecting the coastal state’s fisheries rights in the short term.

Anyone involved in international law, multilateral consensus building, and the development of norms will be unsurprised by my assessment of the road ahead - it will, in all likelihood, be made up of incremental steps and involve a fair few unsatisfying detours.

And yet, we are optimistic that with goodwill, perseverance and a strong Pacific voice, we can make meaningful progress to ameliorate this perverse outcome and safeguard the hard-won resource rights that are so essential to the Pacific region.

Or to borrow from an appropriate whakatauki: He moana pukepuke e ekengia e te waka: A choppy sea can still be navigated.